Puerto Rican New Yorkers: Revolts and Riots

Introduction

“Puerto Rican” urban revolts and riots originated in the experiences of concentrated urban poverty and oppressive policing in US “ghettos”that many Puerto Rican migrants and their US-born children confronted (sometimes together with Latinos of other backgrounds). These riots were not restricted to New York City. Most urban centers with large numbers of Puerto Ricans experienced a riot or large confrontation with police sometime in the 1960s or 1970s, including multiple cities in New Jersey and Connecticut.

The scholarship on Puerto Rican riots is not extensive. The only scholars who have examined Puerto Rican participation in post-WWII riots in any detail are Olga Wagenheim, Michael Staudenmaier, and Llana Barber.[1] This essay reviews some of the evidence and narratives about a few of these riots and confrontations. Elsewhere, I review the New Jersey Riots. One of the motivations for this review is to promote locally focused research with richer sources for these events and how they might relate to the larger community histories. The other is encouraging more focused research into policing practices and police-community relations. Focusing on riots tends to be polarizing and perhaps distorts other relationships of the before and after. An additional intent is to deromanticize these violent confrontations and broaden the scope beyond police/Puerto Rican youth to include third and fourth parties, including the older parents and grandparents of the younger people (usually men) involved in these stories. There is also the need to study the larger local and community dynamics that led to these confrontations and the larger contexts that frame these violent events.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, police-crowd conflicts were common in Harlem and other predominately black neighborhoods policed by overwhelmingly white policemen. Crowd responses to arrests, abuse, or confrontations with police could lead to larger conflagrations, sometimes with hundreds of participants. Sometimes, the conflicts would start between Black, Italian, Irish, and Puerto Rican youth, perhaps gang members. Still, these fights would lead to larger conflagrations when police arrived and become confrontations with the police. During the 1960s, riots became more common, essentially the product of the intersection of policing, racism, and concentrated urban poverty. But we know little about the narratives and causes of most of these riots.

In New York, the tensions between Puerto Rican barrio youth and the police increased when a policeman killed two Puerto Ricans on November 15, 1963. Victor Rodriguez and Maximo Solero were arrested for disorderly conduct. Police claimed that one of them pulled a gun while under arrest in the squad car and that the shootings were justified. The officers were not charged. Doubts remained about the story, and public protests were held, including pickets at the local Upper West Side precinct, organized by the recently formed National Association for Puerto Rican Civil Rights.[2] Weeks later, in February 1964, an off-duty policeman killed a fleeing Puerto Rican youth after he intervened in a fight outside a bar. The funeral of Frank Rodriguez led to angry outbursts and charges of police abuse. Community leader Gerena Valentin accused some police of acting “as if they were running a plantation.”[3] These events, and many others that have not been well documented by historians, led to increasing tensions and led community leaders to further alarm about how certain neighborhoods and Puerto Rican people were policed.

In New York, the tensions between Puerto Rican barrio youth and the police increased when a policeman killed two Puerto Ricans on November 15, 1963. Victor Rodriguez and Maximo Solero were arrested for disorderly conduct. Police claimed that one of them pulled a gun while under arrest in the squad car and that the shootings were justified. The officers were not charged. Doubts remained about the story, and public protests were held, including pickets at the local Upper West Side precinct, organized by the recently formed National Association for Puerto Rican Civil Rights.[2] Weeks later, in February 1964, an off-duty policeman killed a fleeing Puerto Rican youth after he intervened in a fight outside a bar. The funeral of Frank Rodriguez led to angry outbursts and charges of police abuse. Community leader Gerena Valentin accused some police of acting “as if they were running a plantation.”[3] These events, and many others that have not been well documented by historians, led to increasing tensions and led community leaders to further alarm about how certain neighborhoods and Puerto Rican people were policed.

The materials presented here suggest an integrated approach to urban conflicts as they present not only what has been traditionally described as gang warfare (rumbles) but also episodes of large-scale confrontations involving both police and youth from more than one ethnic/racially identified group.

A (Working) List of Puerto Rican Riots, Revolts and Large-scale Confrontations

New York City

- East and Central Harlem,1920s, riots/turf war involving Jewish merchants

- Harlem, 22 August 1929; Blacks vs. PR vs Police

- Lower Harlem, 1931 PR-Filipino street fights/riot

- Central Harlem, 1934, Role of a Puerto Rican boy in riot.

- Chelsea, Summer 1949, anti-Puerto Rican attacks.

- Bronx, 4 September 1956, PR-Police mass fight 17 arrests, shots.

- Location unclear, 16 July 1957.

- Harlem, Black-PR mass fights, 14 July 1959

- Early 1960s, multiple mass confrontations with black youth and Police

- Bronx, 24 July 1961, Bronx 500 vs 50 cops

- Upper West Side July 6, 1961 riot Blacks/PRS.

- Brownsville, 22 July 1961

- Brownsville, August 1964, Black vs Puerto Rican “gangs”

- Lower East Side, 29-30 August 1964, Black-PR fights, 100s involved.

- Harlem, July 1964—PR involvement.

- East Harlem, 1965

- East New York, 15-18 July 1966, Black/PR/Italians three-way conflict.

- Bedford Stuyvesant, 1966

- Lower East Side, 1967.

- Bronx; Summer 1967; 138th and Willis St.

- East Harlem, July 1967.

- Lower East Side, July 1968.

- Coney Island, July 1968.

- East Harlem, June 14, 1970; Lords involved.

New Jersey

- Hoboken 7 October 1955.

- Jersey City, 7 Sept 1955.

- Elizabeth, July 1967.

- Jersey City, June 1966.

- New Brunswick, July 1967.

- Perth Amboy, August 1966.

- New Brunswick, July 1967.

- Jersey City, July 1967.

- Paterson, June and July 1968; Disturbances, rifles fired.

- Camden, August 16-25 1969.

- Trenton, June 1969.

- Passaic, August 1969.

- Hoboken, June 24 1970.

- Hoboken, Aug 27 1970,

- Newark, July 19 1970.

- Jersey City June 1970.

- Hoboken July 1970.

- Hoboken sept 4, 1971.

- Camden, July 30, Aug 20+,1971.

- Newark, 1974.

- Paterson, October 1971

- Long Branch, 1971.

- Perth Amboy, 1988. Some Puerto Rican involvement, mostly Mexican.

Connecticut

- Hartford 1969

- Hartford, 1970

- Hartford,1971

- Waterford, 1971

- Waterbury, July 1969.

- New Haven, August 1967.

- Bridgeport, September 1971.

Massachusetts

- New Bedford, July 9, 1970.

- Boston, 1972.

- Lawrence,1984; (Llana Barber).

Others

- Spring Garden, Philadelphia, 1953, mass fight whites/Puerto Ricans.

- Buffalo, NY, July 1964.

- Chicago, 1966.

- Buffalo, NY, 1967.

- Westchester, Pennsylvania, July 1970.

- Chicago, June 1977.

- Wynwood, Miami, 1990.

East New York 1966

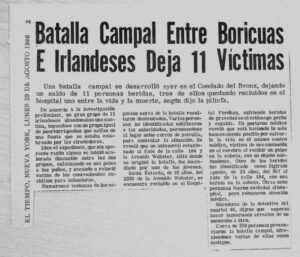

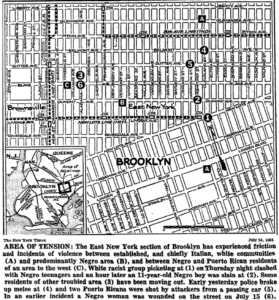

Clashes between African-American and white youth, and later, between African-Americans and Puerto Ricans in East New York in the summer of 1966 turned quickly into battles against the police. After a series of nightly confrontations between Puerto Rican and Black youth in July, Mayor Lindsay met with fifty community leaders who promised to help keep the neighborhood cool and calm in “the racially tense half square mile area.” After the events of the previous evening, a massive police presence in the neighborhood streets was accompanied by ministers. These officials from local anti-poverty programs and community relations officers attempted to mediate among the “dissidents,” a reference to more militant leaders. The Police Commissioner patrolled the area and thanked parents for keeping their kids home. Friday night and early Saturday morning, five people were arrested, and five were injured in ongoing fights. Later, 150 police officers gathered for eight hours to quell an angry crowd, urging pedestrians to stay off the streets and move quickly whenever they felt a crowd would form. At one building, police dispersed a crowd as shots were fired, Molotov cocktails and bricks thrown at the police. These ongoing conflicts also included white gang members. In one building, black residents feared attacks from white gangs and reported that: ”whites drive by that point their fingers like pistols and they holler bang bang, nigger your dead and clear the streets niggers.”

Police and youth workers continued to disperse crowds whenever they formed, and Molotov cocktails were occasionally thrown. Over the weekend, at least 1000 extra police were deployed to the area, including 350 elite tactical patrol force members and a squad of mounted patrolmen. Bottles, bricks, firebombs, chases, rooftop pursuits, flying broken glass, false fire alarms. All part of the scene, but no looting took place. On Sunday, quiet prevailed.[4]

We don’t know what triggered these confrontations or how they related to further clashes in the 1960s. Certainly, this story demonstrates the complex layers of these confrontations but also signals a transition from conflict centered on inter-youth issues to police-youth confrontations.

Chicago 1966

Perhaps the best-known Puerto Rican riot (or barrio revolt) did not take place in New York but in Chicago’s near-Northwest side after police shot a Puerto Rican youth in June 1966. The riot started when police responded to an argument between a tenant and his landlord at a nearby pool hall. However, there are also alternative stories about the immediate trigger for the riot. About 1000 people were involved in the disturbance while many hundreds more came to the area to watch at the intersection of Damon and W. Division St. When police released a trained dog and it bit a 20-year-old, the conflagration intensified. An additional 100 policemen were called. Around 10 PM, 400 people remained in the area. Bricks and bottles were thrown at police cars, and some were set afire, while firemen responding to the fires were attacked. One journalist was attacked by the crowd but was rescued by other Puerto Ricans from the neighborhood. A fire hose was taken from firemen and used against the police. Spanish-speaking policemen were called to speak to the crowd with bullhorns while local community leaders tried to calm the crowd, including Rev. Donald Headley.

Violence began again that evening, with youth throwing rocks and smashing cars in store windows and traffic lights, doing some looting, and “harassing” the police. The police response was more intense. Seven people were shot and others injured in the second night of rioting on Division Street. Community leaders were now asking the police to leave the area and allow them to keep the peace, and apparently, the police did withdraw their cars. A rally of 1200 people at Humboldt Park was organized and some of the speakers made charges of police brutality. But rioting continued after the event, and police returned, dispersing crowds with clubs and firing several shots. Men injured by the police returned to the streets complaining of the use of force: “we are not supposed to be beat up like animals.” As squad cars drove by a young man yelled with fists raised in anger: “Police, go home, get out!” Community leaders, again, came out this time with ribbons of red, white and blue so the police could identify them (and presumably not beat them up). Police and crowds continued to mingle into the second evening, but it was clear that besides the initial incidence of the shooting and the anger created by the use of dogs, the very presence of the police continued to strengthen the response from the youth.

After the riot police ordered an ‘integration’ of police crews in order to spread out the presence of minority officers, to expedite the removal of dogs from disorder scenes, and appoint a black commander, the officer responsible for inciting the riot was moved to another district, with the acknowledgment that he was known for “starting trouble”—this led to his resignation. Community leaders agreed “that police tactics in the neighborhood had long been unnecessarily severe.”[5]

East Harlem 1967

Police abuse was again the immediate motivation behind the July 1967 riot in East Harlem, when El Barrio experienced three nights of melees with about 2000 rioters involved. The riot was triggered by the police and aimed at an off-duty policeman who killed a Puerto Rican he claimed was holding a knife. The killing led to a revolt of the neighborhood’s young people, who smashed windows and looted in a riot not as extensive or damaging as those of other cities or even the larger 1964 and 1968 Black Harlem riots.

The riot began on July 22nd, in the hot, humid days of summer, with many people out on the streets because of the heat. It continued on the night of July 23, as further violence broke out in East Harlem on 111th St. One thousand police were mobilized and shots were fired, police cars attacked and windows smashed, with only a small amount of looting on Third Avenue. Police claimed a sniper on a rooftop shot at them, and they responded with 15 shots. Roving crowds attacked police cars with stones and bottles throughout the whole area.

On the first day of the confrontations, two people were killed by police bullets, and police attempted to cover up both (police initially claimed a .22 bullet note fired by them and a broken neck were the causes of death). Police shot Emma Haddock, a respected member of the local Community Council, while she looked out her window. The other victim was Luis Antonio Torres, 22. The killings only angered local people further.

Mayor Lindsay agreed to a meeting with the police commissioner at a local church, where a truce was organized. The tactical police units withdrew, but the confrontation continued. When the tactical police force reappeared, some leaders felt betrayed, and their work of calming the crowds became more difficult. Into the morning, groups of patrolmen attacked crowds of youth on E. 108th St. Police claimed, and journalists supported, that they swung at their butts and not their heads–a command given by Mayor Lindsay not to fire or attack protestors. On Third Avenue, several hundred youths came out, blocking the street and prancing with a dressmaker’s dummy, giving the simmering events a festive tone. The police “surged“ through the crowd and bottles flew from rooftops and crashed all around them. The Police Commissioner claimed he was not happy about the use of clubs to disperse teenagers, a marked contrast with the full military response in Newark and California riots, which brought out National Guard units. Some police officers began asking the youth to go home. The New York Times noticed that on the first night of violence, it was the very presence of the police, and especially the tactical police force, that was the target of the youth. Beatings by the tactical police on the first morning of the riots only led to further violence. It took additional reinforcements to disperse people by 5 AM on the first night.

The first night of the riot, The New York Times reported a man haranguing from a stand made of garbage cans on Third Ave and 111th St. He made short speeches in Spanish about Puerto Ricans serving in Vietnam: “something is owed to us”…and incited a group, resulting in an attack on a nearby gas station. At midnight, a group of youths carrying a Puerto Rican flag tried to march on the East 104th St. police station but were turned back by the tactical police force.

As ordered by the mayor after the first night, police were apparently successful at minimizing arrests and not using their guns. Every shop on Lexington Ave. between 102 and 103rd had been broken, and crowds were busy looting, burning trash along the way, and taunting police from stoops and doorways. Running confrontations between youth groups and police cars continued, with looting resuming as soon as the police passed.

During the second night, police tried to appease crowds gathering on 109th and Third Ave. The agreement from the first day kept them from using sirens, wearing helmets, or using helicopters to hunt for rooftop brick throwers. At some point in the confrontation, some youth drew a chalk line across Third Ave just above 110th St. and wrote, “Puerto Rican border. Do not cross, flatfoot.” The line, as much a boundary for police, indicated the ethnic divisions of East Harlem, with the areas east of Third Ave. still being predominantly Italian. The New York Times had no problems acknowledging that the conflict came from the brutality of some police, the contempt and the ethnic slurs of others, and the frustration of officers not being able to speak Spanish, as well as the cultural differences that led Puerto Ricans to “gather nightly on sidewalks and stoops to drink beer and talk” as an acceptable part of daily life.

The mayor showed up the morning after the first night of rioting, having come from out of town. He was well received and cheered, and for more than two hours as he listened to delegates not commenting on police brutality. Some community leaders expressed relief that the mayor was sympathetic and would help them reach “those damn cops.” The Mayor refused to blame outside agitators and called for Spanish-speaking policemen to be assigned to each precinct with large Puerto Rican populations. A police order circulated quietly reminded policemen not to use derogatory racial language. Anti-poverty workers also worked to ensure that other parts of Harlem did not break out in violence.

But despite the Mayor’s very positive reception by residents and community leaders in East Harlem, looting and rioting continued. On the third night of clashes, the youth continued in the streets, and the mayor and other leaders were at a loss as to how to respond. At the same time, the disturbance extended to the South Bronx on the night of July 24th, resulting in a 19-year-old shot in the arm on 139th St. and rampaging groups of youth setting fire to trash cans, with two stores looted. 70 police were mobilized in that area. A few days later, when a dozen youths became angry at a policeman for halting their stickball game, 75 participants joined in some sort of conflagration. In response to the violence in the Bronx, priests and nuns organized a procession starting at the Catholic church on East 138th St. Monsignor Fox gathered thousands for this procession, with crucifix, vestments, incense, and candles, calling on people to join in prayer and song. This worked.[6]

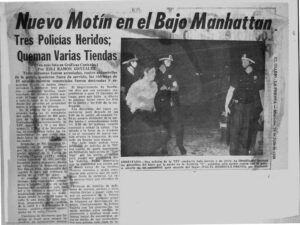

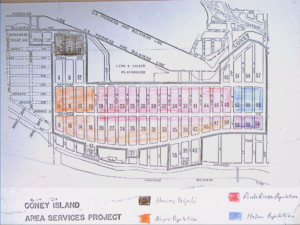

Coney Island in 1968

Coney Island experienced a protracted conflict in July 1968. Starting on the 19th (?) and for various days, the predominantly Black and Puerto Rican blocks broke out into fighting with police and attacks on property. On the 22nd, police were beaten by a crowd in a resurgence of confrontations, but the deployment of the TPF dispersed the youth. Mayor Lindsay acknowledged that the situation in Coney Island showed no improvement after four days of conflict, but he described it as a conflict in which blacks and Puerto Ricans were fighting whites (with the cops in between). He toured the area on the 23rd, hosting meetings with local people.

Violence continued through the 21st, when police were attacked and beaten by a crowd of several dozen people, throwing bottles and Molotovs. The TPF was sent to clear the streets. Friday, youths wrecked a local luncheonette owned by a local Puerto Rican woman and used by police as a base. Meetings of city officials and members of the community ended with promises that the TPF would not harass people working with the anti-poverty programs or attack the “community action centers or the people inside them.”[7]

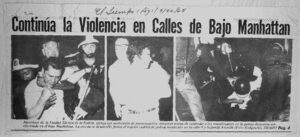

Lower East Side: also 1968

The following year, it was the Puerto Rican blocks of the Lower East Side that erupted at the same time as the Coney Island riots. In these events, the community’s intense rejection of the Tactical Police Force became a central part of the story. During July 1968, fires were set, and cars and storeswere attacked on 5th St. between avenues B and C. On the 22nd, a Puerto Rican (Victor Soto) launched three firebombs into a Lower East Side bar (Jack and Joe’s Bar and Grill) at 9th and Ave. C, apparently for the beating of a paisano at this bar.

The riot started with fights between PRs and Eastern Europeans on Friday night at 9th and Ave C. Police responded but were attacked when they tried to disperse the crowd watching. A local priest was not able to stop the initial confrontations. The riot started at 9 pm on Friday 23rd and lasted through Tuesday, on 9 blocks from 2nd to 10th St. and Ave C, with at least 200 youth. On the first night, four police cars were destroyed, shops were attacked, and 13 were arrested. 400 police were mobilized, while 600 citizens came out, angry at how the Tactical Police plaice had been mobilized the previous night. Bottles and gunshots were aimed at the police. Police and firemen were wounded.

Residents sent a message to the police that there would be no peace until the TPF was removed. Police opened fire from behind their cars on Ave C and 6th St., firing 15 shots at what they thought were rooftop snipers while bottles rained over them. The local Catholic priest described events this way: “todo empezo cuando la Unidad Tactica se presento frente de la cantina del 144 y la ave C el domingo por la noche arrestando a dos hombres lideres de la cuadra. Desde ese momento los hispanos se revolvieron en contra de esos oficiales.” A committee of local activists secured a commitment on the 24th that the TPF would be withdrawn. Gerena Valentin concluded that the TPF destroyed in one day the work that the precinct achieved by arresting and beating up people unnecessarily: “their whole attitude is that we are foreigners.” Leaders walked the streets on the 24th as street life became more normalized. The community was united in rejecting the TPF and the unilateral demand to withdraw it. But as in other riots the community leadership was divided, some acknowledging that there were local, grassroots groups that “[did] not accept the leadership of any committee.” On the final day of the disturbance, Tuesday, a peace march led by Catholic seminaristas, carrying pictures of Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Hubert Humphrey and a sound truck playing Puerto Rican music marched in the area, stopping at C and 6th st. Down the streets more bottles rained down on the police and police charged the group…”cerdos fascistas” yelled the crowd…but calm was reestablished by 11. By the 27th, with the withdrawal of the TPF things returned back to normal. “They took the TPF out that’s what happened.” Many shop owners had their businesses damaged or destroyed, many of them Puerto Rican, some of them accusing the police of not doing enough to protect their property.[8]

A committee of local activists secured a commitment on the 24th that the TPF would be withdrawn. Gerena Valentin concluded that the TPF destroyed in one day the work that the precinct achieved by arresting and beating up people unnecessarily: “their whole attitude is that we are foreigners.” Leaders walked the streets on the 24th as street life became more normalized. The community was united in rejecting the TPF and the unilateral demand to withdraw it. But as in other riots the community leadership was divided, some acknowledging that there were local, grassroots groups that “[did] not accept the leadership of any committee.” On the final day of the disturbance, Tuesday, a peace march led by Catholic seminaristas, carrying pictures of Kennedy, Martin Luther King and Hubert Humphrey and a sound truck playing Puerto Rican music marched in the area, stopping at C and 6th st. Down the streets more bottles rained down on the police and police charged the group…”cerdos fascistas” yelled the crowd…but calm was reestablished by 11. By the 27th, with the withdrawal of the TPF things returned back to normal. “They took the TPF out that’s what happened.” Many shop owners had their businesses damaged or destroyed, many of them Puerto Rican, some of them accusing the police of not doing enough to protect their property.[8]

Chicago again 1977

Chicago’s Puerto Rican 1977 riot has received little notice. Looting and fighting broke out on June 4, 1977. Two were killed. The first night, 70 were injured, including 28 policemen, while 119 were arrested. A Puerto Rican celebration at a park led to fights between gangs (Kings vs Cobras). For six hours the fights spread to the neighborhood and then turned to fights between local people and the police with looting and two major fires. Different accounts explained how things escalated. Police claimed that one man fired shots at two officers, missing them but wounding another Puerto Rican man. Police shot and killed him. The police then tried to close the park but were “met with a barrage of bricks, bottles, stones, sticks, and chairs. Puerto Rican witnesses claimed that the police had stormed the park, attacking all people indiscriminately. Police were not able to control the ensuing rioting and burning. Dozens were injured, and two were killed. On the second day, police grouped throughout the area while city crews cleaned up, but more confrontations broke out on the 5th. Youth attacked police with bottles and rocks and looted along Division Street. Gangs and tremendous tension between black and PR students at a local high school were cited as contributing forces. The Cobras, the Kings, the Mozart Pimps and the Latin Stones. The usual ghetto problems of lack of jobs for youth and adequate housing were mentioned by community leaders who met on the afternoon of the 5th.[9]

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Barber, Llana. Latino City: Immigration and Urban Crisis in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1945-2000. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017; Staudenmaier, Michael J. “Between Two Flags: Cultural Nationalism and Racial Formation in Puerto Rican Chicago, 1946-1994.” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2016.

[2] The New York Times, 18 January 1964.

[3] The New York Times, 29 February 1964.

[4] The New York Times, 24 July 1966, 25 July 1966; El Tiempo, 20 July 1966.

[5] JET 1966; The New York Times, 13 June 1966, 29 July 1967.

[6] The New York Times, 24 July 1967, 25 July 1967, 26 July 1967, 27 July 1967, 29 July 1967, 30 July 1967, 31 July 1967, 30 September 1967; Joseph Fitzpatrick, Memoir (manuscript), Box 46, Folder 1, Papers of Joseph Fitzpatrick, Special Collections, Fordham University; “Policemen clear in 2 riot killings.”

[7] The New York Times, 22 July 1968.

[8] El Diario/La Prensa, 7 July 1968, 25 July 1968, 24 July 1968, 23 July 1968, 25 July 1968; El Tiempo, 27 July 1968, 23 July 1968, 26 July 1968, 24 July 1968; The New York Times, 26 July 1968, 27 July 1968.

[9] The New York Times, 6 June 1977.