Puerto Rican New Yorkers: New York’s Cigarmakers, 1910s-1930s

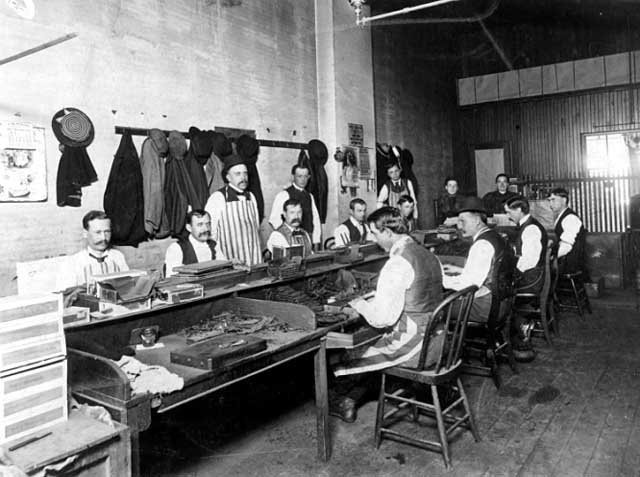

For centuries, tobacco growing, processing, and cigarmaking were part of Puerto Rico’s history. Hand-rolled cigar production by men (and a few women) was an important trade of skilled artisans during Puerto Rico’s Spanish colonial period and experienced a resurgence during the first twenty years of US rule when US corporations took over the island’s expanding trade in tobacco leaf. Puerto Rican cigarmakers migrated in large numbers to New York and Florida, joining the Cuban and Spaniard cigarmakers who had been migrating to New York since the 1860s and who had established themselves firmly in the industry before the Puerto Ricans started arriving in the 1890s. In New York and Tampa, they formed part of a Hispanic and Southern European immigrant working class. Cigar making was the only industry where Latino workers confronted Hispanic bosses—Samuel Gompers estimated that of the 3,000 cigar factories in New York, at least 500 were owned by Spaniards and Latin Americans.[1]

For centuries, tobacco growing, processing, and cigarmaking were part of Puerto Rico’s history. Hand-rolled cigar production by men (and a few women) was an important trade of skilled artisans during Puerto Rico’s Spanish colonial period and experienced a resurgence during the first twenty years of US rule when US corporations took over the island’s expanding trade in tobacco leaf. Puerto Rican cigarmakers migrated in large numbers to New York and Florida, joining the Cuban and Spaniard cigarmakers who had been migrating to New York since the 1860s and who had established themselves firmly in the industry before the Puerto Ricans started arriving in the 1890s. In New York and Tampa, they formed part of a Hispanic and Southern European immigrant working class. Cigar making was the only industry where Latino workers confronted Hispanic bosses—Samuel Gompers estimated that of the 3,000 cigar factories in New York, at least 500 were owned by Spaniards and Latin Americans.[1]

The best cigar work, known as “out-and-out,” was a fully manually made cigar. Because of their connection to Caribbean methods of tobacco production, Spaniards, Cubans and Puerto Ricans were especially skilled at making these cigars with few tools, using only a knife and a board.[2] This skill made it possible to work quickly and to roll cigars anywhere and anytime, in a small shop or a large shop. Typically, they were paid by piecework, not hours worked. Cigarmakers considered themselves skilled artisans who took pride in their trade. However, the invention of the suction machine in 1917, which could produce cigars more quickly and more cheaply, began the displacement of hand-rollers throughout the industry in the US, as well as the Caribbean.[3] After WWI (1914-1918), the industry in Puerto Rico began to decline. Thousands of hand rollers lost their employment—reduced from 30,000 in 1918 to 7,000 in 1936. Wages also declined from a dollar daily in 1910 to $.32 -.57/day.[4] Many of these skilled workers, whose unions had been brought into the CMIU (the main Cigarmakers union in the US, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor) found that migration offered the hope that they could continue their trade in the US, where both cigar consumption and wages were relatively higher.

Next: Cigar Workers Strike of 1919

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1] Falcon, Angelo. “The History of Puerto Rican Politics in New York City: 1860s to 1945.” In Puerto Rican Politics in Urban America, edited by James Jennings and Monte Rivera. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1984, 15-42.

[2] Killough, Lucy Winsor. The Tobacco Products Industry in New York and Its Environs; Present Trends and Probable Future Developments. New York: Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, 1924, 20.

[3] Killough, Lucy Winsor. The Tobacco Products Industry in New York and Its Environs; Present Trends and Probable Future Developments. New York: Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, 1924, 22.

[4] Juan José Baldrich, “Gender and the decomposition of the cigar-making craft in Puerto Rico, 1899-1934,” in Matos Rodríguez, Félix V., and Linda C. Delgado. Puerto Rican Women’s History: New Perspectives. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1998; Tirado’s data provides a more extreme contrast: $2.50/day in 1918, 5174 cigarmakers in 222 shops; and 9852 female strippers, the vast majority non-union; 1300 in 1913 in the union. Tirado, Amilcar. “Cigar Workers and the History of the Labor Movement in Puerto Rico, 1890–1920.”, Ph.D. Dissertation. City University of New York, 2012, 195-6.