Puerto Rican New Yorkers: A Middle Class of Empire, 1900-1929

As soon as Puerto Rico’s new relationship as a colonial territory of the US was established after the US invasion of July 1898, migrants drawn from Puerto Rico’s elite and middle-class sectors began to settle in New York City. These migrants were merchants, professionals, and administrative staff who formed part of Puerto Rico’s growing participation in the commercial networks that connected the island to the US’s Northeastern cities, especially New York. The growing investments by US companies in agricultural commodities, alongside growth in trade facilitated by the Jones Act, provided opportunities for Puerto Rican merchants, investors, intermediaries, and white-collar workers. They joined a small, dispersed group of mostly cigar workers who had migrated (especially via South Florida) to New York in the 1890s and very early 1900s.

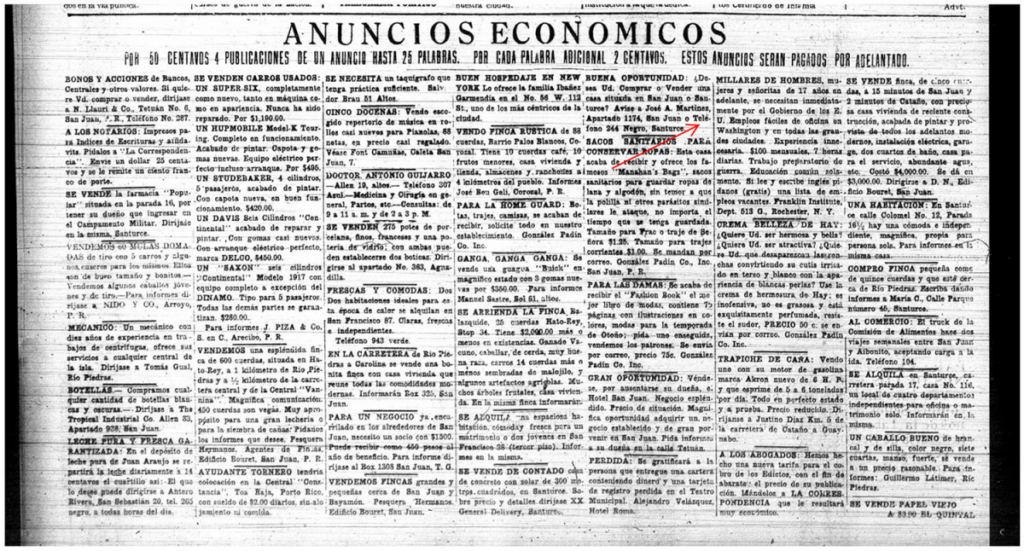

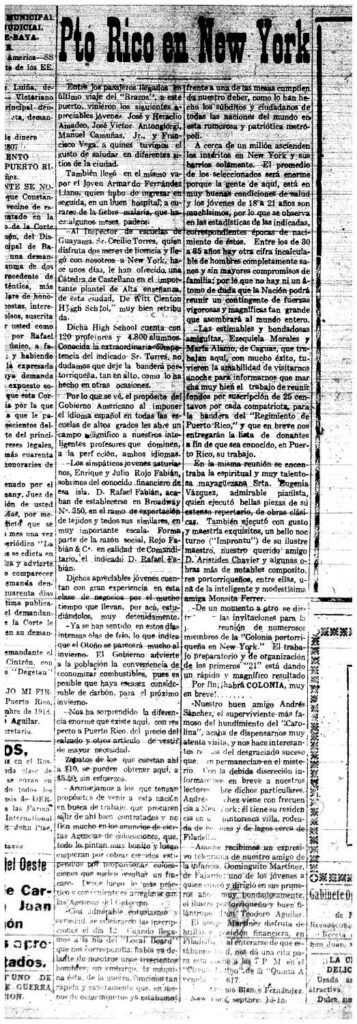

The island’s newspapers tracked the social lives and commercial successes of these middle-class and elite migrants who worked as agents, clerks, accountants, shippers, and business owners. Before the imposition of US citizenship in 1917, citizenship was not required for Puerto Ricans to travel and reside as US “nationals,” insulated from legal controversies, a legal status that activists from this very class helped solve through religious action.[1] They mostly lived dispersed throughout Manhattan and could express surprise when they randomly stumbled upon each other in the City’s streets. They frequented familiar Spanish restaurants and local markets.[2] Visitors from Puerto Rico estimated that there were about 1500 Puerto Ricans in New York in 1918. Still, this estimate likely did not include the rapidly growing ship, cigar, dock, and factory workers settling in West Harlem, East Midtown, and Brooklyn’s Red Hook.

These middle-class and elite migrants predominated until the final years of World War I, when the recruitment of workers in Puerto Rico began to reconstitute migration to New York City towards the working class. However, the influx of elite and middle-class Puerto Ricans remained a part of both the migration process as well as the communities in New York and, eventually, in California.

Puerto Rico-Born Population in the US

1910 554

1918 1,500 (estimated)

1920 7,364

These early middle-class migrants were part of the island’s agricultural, professional, and commercial sectors. They were often children or grandchildren of Spaniards or other Europeans who migrated to Puerto Rico during the nineteenth century. As a result, many were comfortable with both the island and Spanish identities.

These (usually young) members of the island’s small elite and middle-class families frequently found means (however temporary) to advance their careers and find their fortune in the City’s job market. Manuel Garcia, a young poet, found a good job in a “famosa corporacion, donde es muy estimado y mejor retribuido.” Armando Lopez Landron ran a family-owned business in Jersey City after joining the US Army during WWI via Puerto Rico’s Camp Las Casas.[3] Another migrant had a shoe export business with his family—a young man for whom residence in New York linked him to his parent’s Asturian background: “el alma commercial un tanto yanquizada, pero el corazon es cada dia mas Asturiano.” Yet another “Asturiano” from Puerto Rico had established a textile export shop in the city. At the same time, a Caguas tobacco grower and merchant, J. Sola, had commercial offices and warehousing in New York. Antonio de Leon owned cigar factories in the city. Caguas’s ex-mayor (a growing center of tobacco production) also had many of his children placed in lucrative jobs in “casas comerciales.” Another islander exported liquor, and yet another was a newspaper cartoon designer. Doctors, bankers, and commercial agents had flourishing practices, while many other islanders visited on business trips.[4]

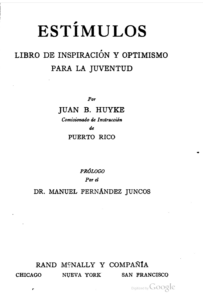

Puerto Rico politician and educator Juan Huyke narrated his random encounters in an early 1920s ship voyage to New York. On the ship he met various teachers, a doctor, someone at the literary digest, two who were placed with a Wall Street company, and a medical school student.[5] Spanish-born islander Jose Padin ran the Spanish department of DC Heath Publishing, while Antonio Leon owned a cigar factory. One school official came to teach Spanish at De Witt Clinton High School.[6]

Puerto Rico politician and educator Juan Huyke narrated his random encounters in an early 1920s ship voyage to New York. On the ship he met various teachers, a doctor, someone at the literary digest, two who were placed with a Wall Street company, and a medical school student.[5] Spanish-born islander Jose Padin ran the Spanish department of DC Heath Publishing, while Antonio Leon owned a cigar factory. One school official came to teach Spanish at De Witt Clinton High School.[6]

In 1922, Huyke wrote of the many Spanish teachers, clerks, lawyers, guest house keepers, customs and mail staff, literature professors, and federal employees spread out between New York, DC, and various campuses.[7] These privileged sectors, living dispersed in middle-class areas or among Cuban or Spanish immigrants, were like ships passing in the night in relation to the slowly growing communities of Puerto Rican laborers near the Brooklyn docks, the tobacco workshops, and in south Harlem. Not only did they not share social worlds, but for years after 1917, they were mostly unaware of each other’s presence. As late as 1925, when vibrant working-class organizations and cross-class political clubs had been formed by Puerto Ricans in Brooklyn and Harlem, elite commentators from the island still declared that there were no legitimate Puerto Rican clubs in the city worthy of the name.[8]

Puerto Rican women, although not visible as merchants or professionals, worked in offices as clerks and bookkeepers or worked as teachers, mostly in the commercial and financial districts of downtown New York. It helped that the war years boosted female middle-class hiring, with advertisements on the island for English-speaking clerical and administrative positions in New York and Washington DC, with salaries of $100/month. A group of these women raised funds for a flag for the Island’s regiment during WWI.

Puerto Rican women, although not visible as merchants or professionals, worked in offices as clerks and bookkeepers or worked as teachers, mostly in the commercial and financial districts of downtown New York. It helped that the war years boosted female middle-class hiring, with advertisements on the island for English-speaking clerical and administrative positions in New York and Washington DC, with salaries of $100/month. A group of these women raised funds for a flag for the Island’s regiment during WWI.

Because of these many opportunities (and voting rights when in the US), Huyke commented, from his middle-class perch, that the Puerto Ricans’ US citizenship was fully equal and not second class (“nuestra ciudadania es la misma”).[9]

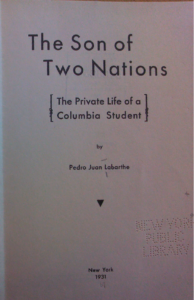

One middle-class story from the 1920s comes from Pedro Labarthe. Pedro and his mother lost their stability to parental separation and the father’s business losses. They had expected a stable life in New York while he attended City College on a $50/month scholarship supplemented by family support. But island authorities could no longer afford his fellowship and both he and his mother had to take jobs. What followed were multiple years of Pedro and his mom weathering factory jobs, illnesses, low wages and evening study. Eventually, Pedro Labarthe finished college, went on to graduate school, and gained a position teaching Spanish and literature at a college. Identifying as the “son of two nations,” Labarthe embraced two identities and citizenships as both an island youth and an immigrant in the US, fused together by the struggles and opportunities he had faced in New York. Later in life he found no contradiction in identifying as a supporter of Puerto Rican independence and progressive New Deal and Popular Front politics, as well as an upwardly mobile product of Puerto Rico’s middle class.[10]

The larger context of 1920s migration was that many migrants came from Puerto Rico’s provincial middle class, sometimes the children of farmers or merchants, and frequently migrating because of a family or personal crisis of downward mobility. One migrant was the son of a coffee farmer whose father employed hundreds of workers, but who chose to escape his father’s expectation that he run the farm. Unable to hold on to his clerical job on the island after expressing his support for independence he migrated to New York.

Some of these professional and middle-class sectors began to concentrate in lower Harlem where they shared a neighborhood with working-class families and eventually organized commercial and professional associations. Most, however, eventually followed the traditional trajectory of higher-earning (and often, white) families to disperse into other neighborhoods—including Hamilton Heights, Washington Heights, and downtown Manhattan—and distance themselves from the emerging working-class barrio cultures of Spanish-speaking New York.[11]

Others shared in a larger Hispanic world in which they were identified as both Spanish and Puerto Rican and shared a direct connection to Spain and Spanish immigrants. Prudencio Unanue of the Goya family shared a Spanish and elite background when he migrated to New York in 1921. Jose Camprubi, an islander born in Ponce from elite Spanish and Puerto Rican parents, studied in both Spain and Cambridge (MA). Camprubi thus circulated comfortably in the pan-Hispanic, Spanish and elite Anglo circles of the Hispanic Society, the Spanish Chamber of Commerce and the Harvard Club[.12] This did not keep him from participating in the Puerto Rican drives for cross-class and ideological unity of the Congreso de Unificacion Puertorriquena in 1938.[13]

Some of these connections to a Hispanic identity rooted in Spain were shared across social classes. ILGWU garment worker Carmen Rosa’s grandfather was from Cadiz [14]. Larry Homar—the artist who built a career first as a red-diaper New Yorker and then as a nationalist islander (Lorenzo Homar)—recalled that his father, who brought his family from Puerta de Tierra in 1928, was “a Spaniard.”[15] James Seix was born in 1915 to Spanish immigrants from Barcelona who had lived in Ponce. Seix went on to become an advertising executive and, during the war, worked as a censor and cryptographer, opening his own firm after the war and hiring many fellow Puerto Ricans.[16]

Many Puerto Rican migrants settled easily into a middle-class life. Irizarry decided to stay with her family in Brooklyn after what was intended as a medical visit in 1922. Already bilingual, she quickly got a job as a stenographer secretary at Amsen Son & Co., where only “Spanish” people worked, and blacks and Italians were excluded. She went on to work at many businesses while studying Portuguese and Italian at night. Her success was as much a product of her skills (and white skin), as from her brother’s support: Luis (Louis) Weber was the boss of illegal lottery in Brooklyn for decades and helped fund and organize some of the most important Puerto Rican political clubs during the 1920s.[17]

Island-based corporations continued establishing offices in lower Manhattan to bridge Puerto Rico and New York’s commercial and financial markets. In 1919, Jose de Jesus, “one of the large financial men of Porto Rico and the head of the Porto Rico Drug Company and several others” leased and renovated four lofts on Broadway for a $50,000 yearly rental.[18]

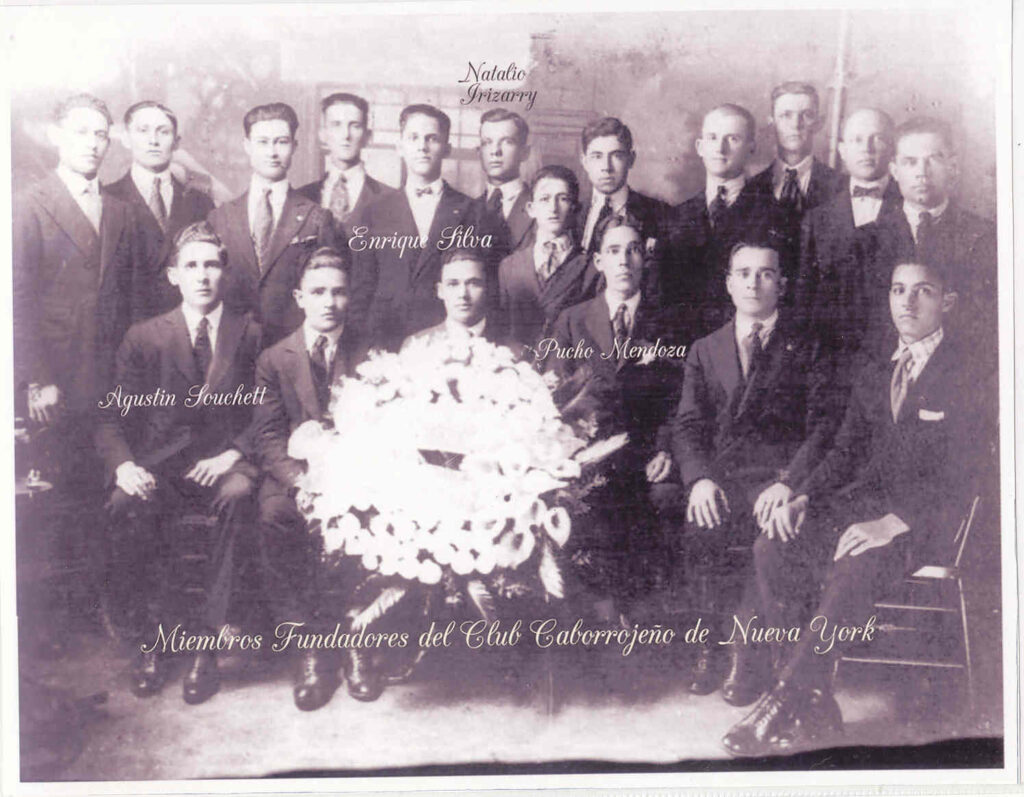

After a few years, some of these middle-class migrants created Puerto Rican-identified organizations, including the Alianza Puertorriquena, founded by this merchant middle-class in 1911 and Casa Puerto Rico in 1924.[19] Eventually, after the community expanded and become more complex politically, these middle class organizations joined as the Liga Puertorriquena. They associated with the Democratic Party, while reproducing in New York political affiliations and affinities followed by elites on the island.

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

[1]Gonzalez vs Williams 1902; McGreevey, Robert. Borderline Citizens: The United States, Puerto Rico, and the Politics of Colonial Migration. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2018; Venator Santiago, Charles. Hostages of Empire: A Short History of the Extension of U.S. Citizenship to Puerto Rico, 1898 to the Present. Editorial Universidad del Este, 2018.

[2]La Correspondencia, various.

[3]La Correspondencia, 23 Sept 1918.

[4] La Correspondencia, various.

[5] Huyke, Juan B. Estímulos; Libro De Inspiración Y Optimismo Para La Juventud. Chicago, New York: Rand McNally y Compañía, 1922. Huyke would soon be serving as Puerto Rico’s first Creole Commissioner of Education (1921-1929).

[6] Like most elite Puerto Rican leaders of the first few decades of the 20th century Padin studied and worked part of his life in the US. Padin would later become Commissioner of Education during the 1930s.

[7] Huyke, Estímulos, 197.

[8] La Prensa, 15 june 1925.

[9] Huyke, Estímulos, 197.

[10] Papers of LaGuardia, Special Collections, New York Public Library; Luis Munoz Marin Papers, Luis Munoz Marin Foundation.

[11] Case #5,WPA interviews, Spanish Book, New York Works Progress Administration Records, New York City Municipal Archive.

[12] Spanish Book, Folder 10- Spaniards 1936, New York Works Progress Administration Records, New York City Municipal Archive.; Adler, Marion F. “Ethnic Changes within the Spanish-Speaking Community in New York City from 1920 to 1930 as Reflected in “La Prensa,” 1964.

[13] La Prensa, 12 November 1938. Feu-López, M. Montserrat. “España Libre (1939-1977) and the Spanish Exile Community in New York.” Ph. D. Dissertation, University of Houston, 2011, 114; Varela-Lago, Ana Maria. “Conquerors, Immigrants, Exiles the Spanish Diaspora in the United States (1848-1948).” Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, San Diego, 2008, 189.

[14] Katz, Daniel. All Together Different: Yiddish Socialists, Garment Workers, and the Labor Roots of Multiculturalism. New York: New York University Press, 2011, 158.

[15] Interview with Larry/Lorenzo Homar, Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[16] Ribes Tovar, Federico. Handbook of the Puerto Rican Community. El Libro Puertorriqueño De Nueva York. New York: El Libro Puertorriqueño, 1968; US Census of Population, 1940. (US Census Bureau).

[17] Interview with Honorina Weber Irizarry, Puerto Rican Oral History Project, Brooklyn Historical Society.

[18] New York Tribune, 29 January 1919.

[19] Sanabria, Carlos. “Patriotism and Class Conflict in the Puerto Rican Community in New York During the 1920s.” Latino Studies Journal 2, no. 2 (1991): 3-16.