Latino Labor History of West New York, New Jersey, 1930-2000

Eleni Boulinaris

Introduction

“Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”(Excerpt from Statue of Liberty inscription)

Hudson County has always been a haven for immigrants because of its proximity to New York City. In the past, Europeans were the predominant population, but with the adoption of the Immigration Act of 1965 that stressed family reunification, the population changed to Middle Eastern, Asian, Latin American, and Caribbean.

With these new immigrants moving into Hudson County, the various cultural identities that make up the immigrant mosaic of Hudson County have also come. The continuous immigration continues today in altering the economic, social, and cultural face of Hudson County’s cities and town.

West New York is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the East, by 66th Street on the north, by Hudson Boulevard West on the west, and 49th Street on the south. There are nine census tracts in the Jersey City Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area, which comprise WNY (c-0052, c-0053, c-0054, c-0055, c-0056, c-0057, c-0058, c-0059, and c-0060).

Northern New Jersey, known for being the Embroidery Capital of the World since 1872, also attracted many immigrants because of the many factories in West New York and Union City. This paper will track the labor trends of the Hispanic population of West New York in detail.

The closeness of West New York to New York City should be kept in mind throughout the paper because many immigrants who lived there commuted to NYC for work.

In West New York, NJ, the most prominent immigrant group for the longest span of time has been the Cuban-American population that fled Cuba during the revolution and began arriving in the 1960s.

Cubans made a major economic impact in West New York as they began to open up small businesses on an economically dying Bergenline Avenue. Cuban refugees turned this town, which some call Little Havana, into a thriving Spanish-speaking community and laid the groundwork for the Latino pan-ethnic population seen today.

Research Process

West New York, NJ, is a small township with a constantly changing immigrant population because of the manufacturing industry and its proximity to New York City. I chose West New York because it is where my family migrated to when they left Cuba, and I was familiar with the area, so I thought that would make it easier to research. This proved to be untrue.

I started my research at the source, the West New York Public Library, which proved to be a complete waste of time. It is a small facility with people yelling, eating, and a reference section that consists of only a few bookshelves. Most of the historical information was from the 1800s and the files of census data and newspaper clippings only went as far back as the 1980s. What I found at the West New York Public Library was a list of embroidery factories in WNY and shops on Bergenline Avenue from the 1930s that I tried to visit, but many of these places had closed down or were under different ownership.

I started this research by identifying the Hispanic population by national origin through census data. In the census data, West New York is listed under the Jersey City Standard Metropolitan Statistical Areas (SMSA) or clumped into a state or county category. This made finding information specific to West New York problematic. West New York is broken into census tracts from c-052 – c-060. Census information for West New York is listed in Appendix I.

With the census data completed, I spent 3 hours a day for 2 weeks in the periodicals room of Alexander micro-phishing and filming through old copies of the New York Times, Jersey Journal, and any other pertinent newspaper in the room – not really sure what I was looking for in the papers. I just kept thinking that there must be a more efficient method for this research, but it seems like most people in the class did the same thing or focused on certain dates that were outlined in the books dealing with the Board of Mediation (West New York was not listed in this series).

I did multiple searches in Iris at the Rutgers library. I was able to find three valuable books that described the assimilation, occupation, and adaptation of Cubans in West New York, NJ, which I read completely. This gave me a fairly decent background of what I was supposed to be looking for but it only covered the Cuban community. What about the other Latinos in the area?

Lupe had referred me to the Newark Public Library, where she was doing most of her research for her thesis on Cubans in West New York and Union City, so I drove out there. My first stop was the NJ room, where the reference assistant pulled out some articles from the Hudson Dispatch and a few books on West New York, but nothing concentrated specifically on the Hispanic population. He did put me in contact with a helpful woman from the Census Bureau that I had emailed regarding a few census questions and told me to try contacting the NJ Department of Labor. I also tried to reach out to the New Jersey Hispanic Research and Information Center, but the reference assistant was going on vacation. She said that she would try to put me in touch with a few students who were in the process of doing research on that area, but as of yet, there was no information that she knew they had on hand.

Luckily, I thought of the Jersey City SMSA and decided to drive to the Jersey City Public Library. I figured I would see what their NJ Room had to offer, and I am glad that I did. The reference assistants, both of which used to live in Union City and West New York, were so excited about the assignment and Rutgers that they pulled out tons of folders of clippings and books. I probably spent 24 hours going through everything and making a ton of copies. (Note: the cops in Jersey City and Newark must have really been in a good mood because I always put a note on my dashboard saying, “Please don’t give me a ticket. Poor college student doing research for a project needs to save all of her change for copies. Thank you.” and I never got a ticket.)

Now, I had clippings, census data, charts, and maps, but I still felt like I did not have enough information.

I had planned on interviewing a few people, but I felt that I would not get any more or any different information than what I had already found in the newspaper clippings, nor did I know what questions to ask. I did stop by a bodega with my grandfather, who had moved to West New York when he immigrated to the US from Cuba. I listened to the stories that the men told of how Cubans transformed West New York into a prosperous city from an economic slump and how the newer immigrants were ruining the Havana on the Hudson that the Cubans had created. While this was not the most scientific or accurate method and offered data that was, for the most part, unreliable, it was able to give me a frame of reference and an idea of what life was like during this time. This gave me a better idea of what to look for when doing research. Although these anecdotes were fun, I decided that it would be more professional and useful not to use them as part of my research.

Back at the Rutgers library, I started to sort out my information and realized that I did not have enough information on what was happening in West New York prior to the 60s. This was the most difficult period to find town-specific data, so I asked the reference assistant for help, and he referred me to the New York Times database online that allows a subject search for everything that has been in the newspaper since 1851 in a PDF file – very convenient.

The writing and research for this paper have given me a newfound respect for the articles that we read this semester because I was able to get a taste of what historians have to deal with when they are piecing together the past with documents that are not as efficient as they are today.

Latino Demographic Trends

West New York, NJ, is a magnet town for new immigrants and has been since the early 1900s when it was home to many Swiss, Austrian, Irish, German, and other European immigrants. This was a prime location for the recent immigrant who did not want the hustle of the city or the homogeneity of the suburbs. Many of the immigrants enjoyed living in a semi-suburban area. This continues to be the attraction that West New York offers recent immigrants; only many more Latinos from Cuba, Puerto Rico, Mexico, parts of Central America, and South America have replaced the Europeans.

What was it specifically about West New York that drew in such popularity with these new immigrants? Why was it that Cubans who spoke no English remembered to tell INS they wanted to go to West New York when they first arrived? In West New York, the rents were low. There were many light industries that always needed help.

As shown in the graph, although there have always been Latinos in West New York, a measurable percentage did not appear until the 1960s with the arrival of the refugee Cuban population that fled communism in Cuba. Prior to the wave that arrived after 1959, there were less than 0.1 percent Cubans and less than two percent Puerto Ricans in West New York so they were not listed separately in the 1960 census. Not until 1968 was there a noticeable surge in the Latino population. (Spector, Barbara Newark Evening News 03-10-68) (Rogg – Adaptation ?)

West New York’s population increased by 14.3%, a numerical increase of 5,080 persons between 1960 and 1970. This increase can be ascribed to the in-migration of Cubans into West New York. In the period 1960-1970, while a net natural population increase of 2,616 occurred, the population increased by 5,080. Thus, there was a total in-migration of 2,464 persons. (Town of WNY Planning Board. “Existing Population characteristics”. Community Housing & Planning Associates, Inc. August 1975.)

The “Population by Hispanic Origin” graph illustrates the population trend of Hispanics in WNY. It shows that the Cuban population peaked in the 80s and has begun to decline since, as more of the original Cubans reached retirement age and migrated south to Florida to be closer to their homeland. With the departure of many Cubans, Mexicans and Central and South Americans began to move into the area. This population did not begin to increase at the current rate until the 90s. This graph also shows a low, constant Puerto Rican population from the 60’s through 2000.

The graph above illustrates the population of West New York from 1900-2000. It shows how the population steadily increased until the 1930s with the influx of European immigrants. The population declined from 1940-1960, as the Europeans began to move after the depression because West New York was in a period of economic decline. The period between 1960 and 1970 showed a sharp increase because of the rampant Cuban immigration, then began to show a slow decline as Cubans began to reach retirement age in the 80s and 90s and started moving to Florida. 1990-2000, another sharp incline represents the new Latino population of South and Central Americans that has replaced the Cuban population.

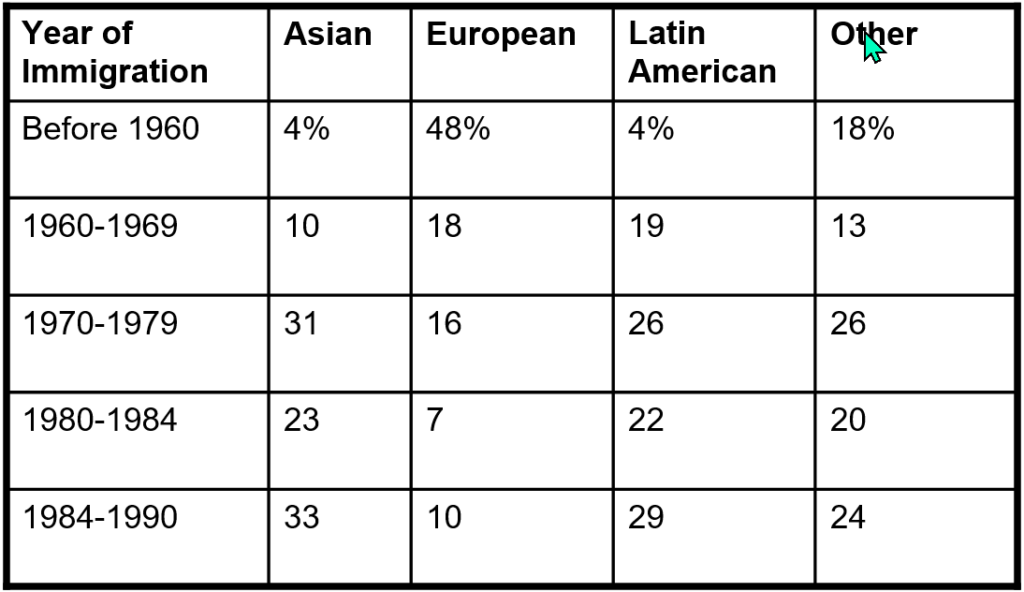

As shown in the table, prior to 1960, the rate of Latino immigration into New Jersey was only 4 percent. Not until the late 60s did the rate of immigration from Latin America make a significant impact.

Class, Occupational, Income/Wealth Data on Latinos

The first wave of Cubans to arrive in West New York came from the middle class of Cuban society, but after that, most Cuban refugees and newer Latino immigrants were of the lower working class.

According to local school officials, the parents of Cuban children always worked and did not want welfare or charity. Cubans made a huge difference in the towns of West New York and Jersey City. (Spector, Barbara Newark Evening News 03-10-68)

“The non-worker/worker ratio is lower among Cubans in 1968 among other West New Yorkers reflecting lower fertility of Cubans, the fact that more Cuban women are working and more Cubans 65 years old and over are working than among 1960 West New York females and aged. Over 63% of Cuban women with their husbands present are working, compared to 48% of other West New York wives.” (Rogg – Occupational Adjustment 135)

In the 1960s, many white Europeans moved to other suburbs of Hudson and Bergen County. West New York’s once prosperous Bergenline Avenue had become deserted, with many storefronts displaying signs for rent or sale. Arriving Cubans were willing to take any job and work for lower wages. Late, they took advantage of the opportunity to open their own businesses, establish factories, industries, etc, realizing that they would not return to Cuba for a long time and should establish roots.

Despite having left Cuba penniless, Castro did not allow anyone to leave with any money or any of their belongings. Cuban immigrants brought with them their ambitions, feelings of success, dissolution from the revolution, and history, heritage, and culture. Their desire and ambition brought prosperity and revenue to the economic scene of West New York.

Cubans were able to invest in shops and such because of the help they received under the 1966 Cuban Adjustment Act, financial assistance from agencies such as the Cuban Refugee Center, religious groups, and character loans given to people based on the way they acted and who they knew in Cuba instead of credit.

Cubans in West New York, NJ, have been able to transform the formerly depressed urban area into a thriving ethnic community and have created a booming real estate market. Cubans added about $350 million a year to the nation’s economy and provided a skilled labor pool. (Pelaez)

“In West New York, the median household income of Cubans rose from $6,118 in 1968 to $13,156 in 1979, as a result of inflation, upward mobility, and the increased labor force participation of married females.”(Cooney 14)

Occupational Comparison of Employable Cuban Refugees Arriving in 1962, 1966, and 1967

| Occupation | (N-27.419)

1962 a |

(N-17,124)

1966 b |

(N-14, 867)

1967 c |

| Professional, Semiprofessional and Managerial | 31 % | 21% | 18% |

| Clerical and Sales | 33% | 31.5% | 35.5% |

| Skilled | 17% | 22% | 26% |

| Semiskilled & Unskilled | 8% | 11.5% | 8% |

| Service | 7% | 9% | 8.5% |

| Agricultural & Fishing | 4% | 4% | 4% |

(a) Recalculated from 1950-62 roster of all employable refugees

(b) Covers the period from 12-01-65 to 12-31-66. Data are from Cuban Refugee Emergency Center, “Cuban Refugee Program, Consolidated Report on Over all Operation, Month of December, 1966”, (January, 1967).

(c) Covers the period from january 1, 1967 to December 19967. Data are from Cuban Refugee Emergency Center, “Cuban Refugee Program, Consolidated Report on Over all Operation, Month of November, 1966”, (December, 1967).

Sources: Fagen, R.. Richard and O’Leary, J. Thomas. Cubans in Exile, California: Stanford University Press, 1968. p. 115

In the 1970s, the Cuban influence could clearly be seen throughout Union City and West New York in the schools, churches, local politics, and the economy. Bergenline Avenue was filled with stores owned and operated by Cuban refugees, signs in Spanish, and the sound of Cuban Spanish was harmonious in the streets. Even the merchandise in the shops was of a higher quality than that offered by the previous owners.

The change in the ethnic character of the North Hudson County region was clearly reflected in the embroidery industry. The once German-Swiss-dominated industry that passed through family lineage had changed in the 1970’s. People of various backgrounds owned the factories, and the workers were largely Spanish-speaking immigrants. An estimated 70 percent of the 10,000 employees in the industry at the time were Cubans and Puerto Ricans in Union City and West New York. (Special to the New York Times. “Looking for Embroidery? Look in Hudson County”. 04-30-72)

Most of the factories that operated in West New York fell under the Schiffli Lace and Embroidery Manufacturers Association. Schiffli is the name of the machine used, the product produced, and the company. This was among West New York’s chief industries. In addition to the Kaywoodie pipe company and a ladies’ pocketbook factory.

In the 1980s, the luck of the Cubans ran out. Cuban refugees roamed the streets looking for jobs that were almost nonexistent. West New York had become one of the densest concentrations of Cubans outside of Miami. They slept in cars and backyards because they were homeless. Some were optimistic about establishing themselves in the United States despite unemployment, lack of housing, and inflation. Others came expecting to make $10 an hour right away after seeing their relatives with three cars, two houses, etc., but these relatives did not tell them that when they arrived 20 years ago, they also started at the bottom.

(Perez Daily News 08-27-80)

More than 119,000 Marielitos had entered the US that April. Between 10,000 and 12,000 refugees were believed to have migrated to the metropolitan area, including 4,000 in New York City. According to Union City Mayor William Musto, city welfare funds had been used up for the rest of the year by August, “How many times are we going to explain it to them? We need help now…” and West New York was most likely in the same situation.

(Perez Daily News 08-27-80)

This new generation of Cubans – the Marielitos – faced many problems in the United States and created resentment within the Cuban-American community, including West New York, where the older Cuban-Americans feared that this new group of immigrants would tarnish the image of Cubans they had worked so hard to maintain. The Marielitos grew up during the revolution and had a different set of values than those who had left Cuba long ago. They were stereotyped as being lazy and expecting an easy life without much sacrifice. This was a very different impression than the Cubans that had arrived in the 1960s and 1970s made in the West New York community.

The main occupations of the Latino groups in West New York were factory and construction work. Many of the Hispanic women worked in the embroidery factories.

In the embroidery industry, shop workers started out as “shuttlers”, placing the bobbins of thread in a steel clasp shaped like the hull of a boat and attached to the needles. Other employees thread the fabric through the top spool or mend patterns when the machine stops because of a jam.

South Americans, Central Americans, and Cubans who came into this industry in the 1970’s joined those who had already been living in these towns. Slowly, many took over the failing businesses of earlier immigrants.

Unions have made a big difference in the wages and benefits of the workers in West New York. Union organizations have brought them benefits and a pension fund so that older employees could retire.

In West New York, for the most part, the top three occupations among the Latino population are:

- Operators, fabricators, and laborers, which includes the manufacturing and embroidery factories

- Technical, sales, and administrative support occupations, which include retail sales occupations

- Service Occupations, which included private household cleaning, among other services

(For further information, see Appendix I: Census Data)

The top three occupations listed above are the occupations with the most Latinos. They represent the working-class demographic of Latinos in West New York, which is mostly working class.

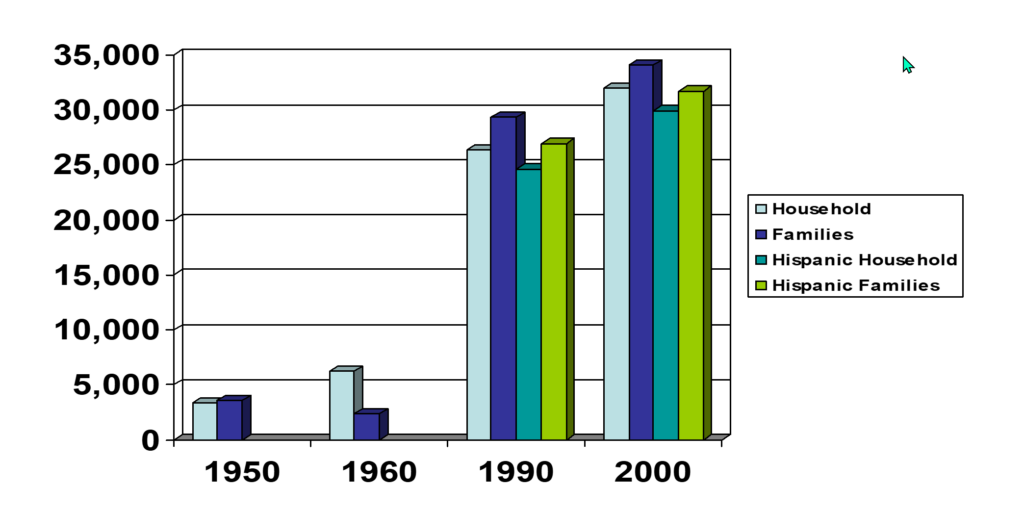

This chart shows that despite the increase in income for the total population. Latinos remain lagging behind in both media household and family income.

Structural and Economic Conditions

What structural, economic, and developmental aspects allowed for the large immigration of Latinos to this 1.3mi2 town?

The economic conditions:

- The white flight of European immigrants who were leaving empty stores behind and moving to the suburbs allowed Cubans, and later other Latinos, to move into the area.

- The labor opportunities available in West New York, New York City, and other surrounding areas attracted immigrants.

- Cheap rent and job availability

- Immigrants normally come from lower economic backgrounds, but two-thirds of the Cuban refugees held middle or high socio-economic positions in Cuba, and over three-quarters held lower positions in WNY. The Cuban’s desire to achieve the status they held in Cuba in the host area motivated them to work hard in WNY to achieve a certain level of success.

The structural conditions:

- Latino immigrants were leaving their war-torn countries, in the case of Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador, looking for more stable living conditions. Cubans came in, fleeing a communist regime in Cuba and in search of better economic conditions.

- In the US, capitalism is the structural condition that keeps Latino immigrants in the low working class. The need to produce products cheaply led to workers being paid below minimum wage, working in sweatshops, and remaining below the poverty line and below the town’s average median income.

- The multitude of factories available within the area of residence so that immigrants could even walk to work, and later, the decline of factories in the area represents the change in the educational attainment of the Latino population.

- The availability of different means of public transportation

Labor Conditions in West New York, NJ

I could not find any large strikes or raids within the town of West New York, but I did come across smaller strikes that WNY employees took part in NYC factories that had shops in WNY. Throughout 1930-2000, there were two main issues of concern in West New York: (1) the decline of the embroidery industry and (2), more recently, sweatshops and homework because of the increasing amount of undocumented Latino workers.

Embroidery Industry Decline:

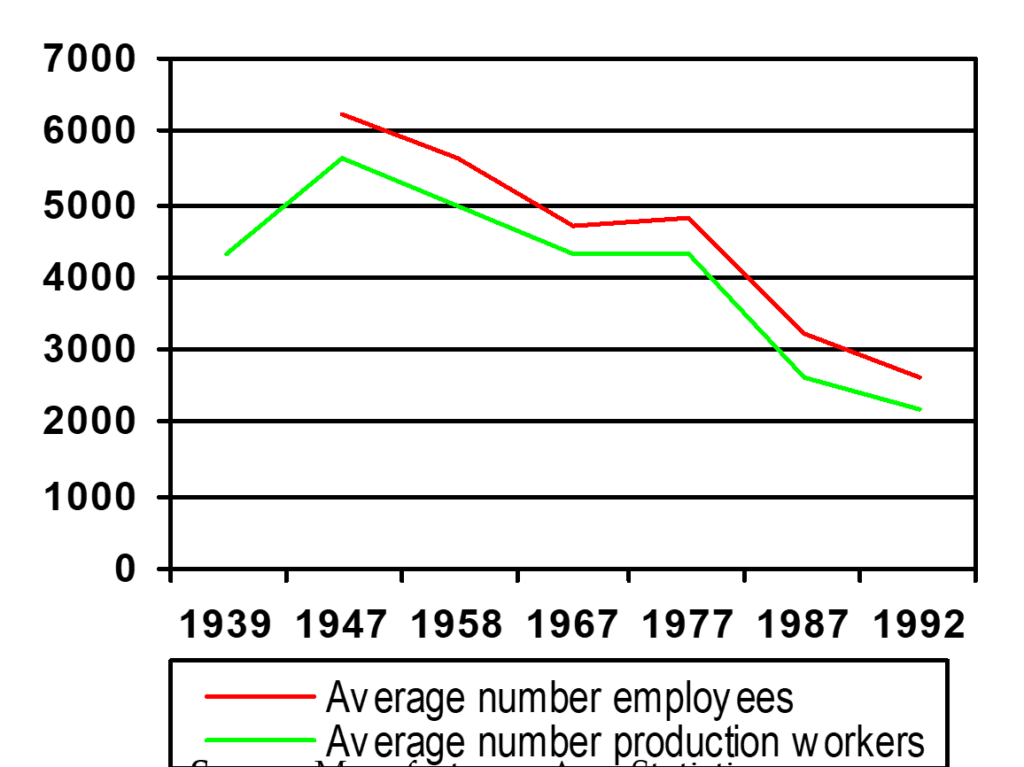

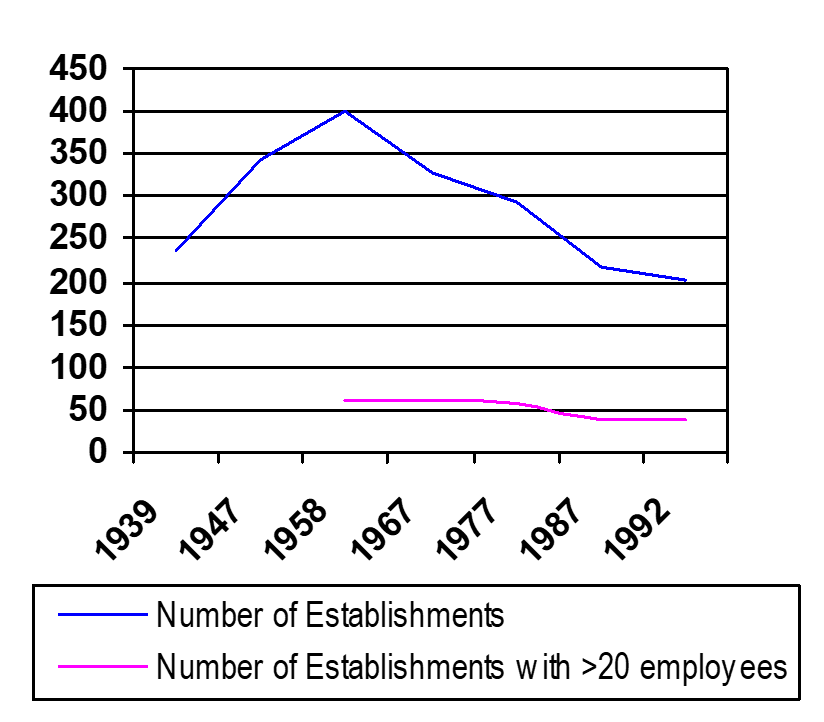

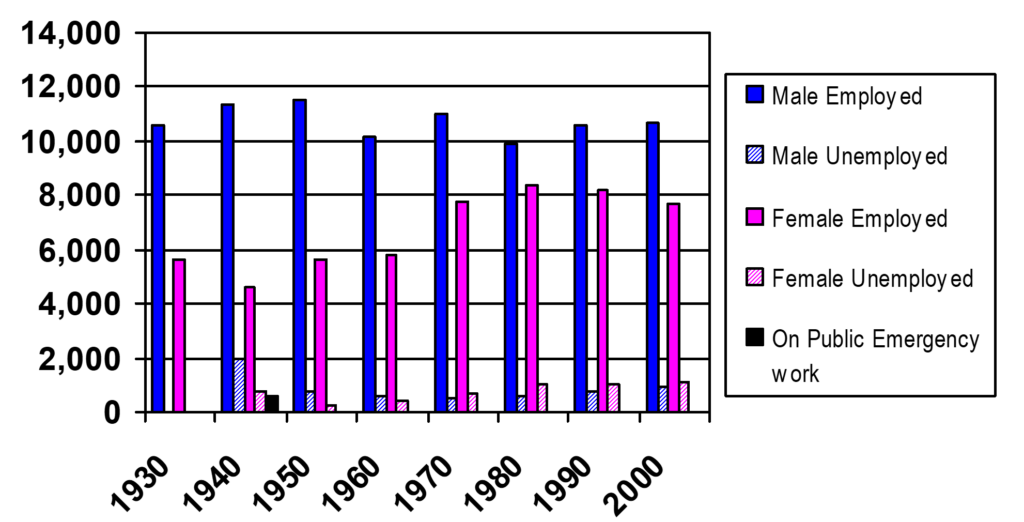

From the 1930s to 1950, many factories in West New York employed a good portion of the resident population. As seen in the two graphs below:

Source: Manufacturers Area Statistics

In the 1940s, West New York surpassed all other towns in the number of embroidery shops. It was the town’s most exceptional industry and its largest economic source. One of its largest accounts was the military and the Pentagon. West New York is where all of the patches that soldiers and officials wear were once embroidered.

For the first time, in 1950, the booming industry was threatened by the increased competition of Third World nations with lenient laws that allowed lower pay for production workers, twenty-four-hour production, lower labor costs, and lower cost of raw materials. The industry was pleading with lawmakers of the House Ways and Means Committee, who were in their third week of deliberation regarding the extension of a reciprocal trade program, which allows companies to import products without paying or paying low tariffs.

But none of this stopped the Schiffli industry. “After a period in which sales advanced from $50 million in 1950 to $75million in 1955 and $110million in 1960, the industry suffered three years of decline.” (Sloane New York Times pg.43)

This is the difficult part of having such a specialized industry, any trend away from the elaborate and the fancy embroidered patterns, has a serious effect on the industry, but trends come and go quickly so many factory owners use the downtime to get ready for the next rise.

The 70s brought back the embroidery trend. Schiffli machines were able to embroider any piece of material that could be pierced. Embroidery was on jeans, leather, seat covers, etc.

The wartime boom that made Hudson County The Embroidery Capital of the World was giving way to cheap foreign competition that threatened many of the businesses with extinction. The remaining businesses are owned by older Central European migrants and newer Latinos who arrived in the 1970’s and now own many of the shops.

Business in Hudson County was down for the Embroidery industry after so many decades of being at the top. Cheaper garments are imported from Central and South America, Taiwan, and Japan. In the 1980s, people in the embroidery industry began to lose more and more jobs every day. Foreign competition is hard to compete with because their labor is cheap, so they are able to charge less. In West New York, many of the companies have resorted to exporting their own products to countries like Mexico for the same price they would have charged 8 years ago. This is leading many of these factories to close or, even worse, claim bankruptcy.

As the embroidery industry began to unravel, Stevens Institute did a study that showed that in northern NJ, the industry is a $300-million-a-year business of 400 companies that employ more than 3,500 people. These are much-needed jobs for first-generation immigrants who are now living in that area.

(New Jersey Business, May 1998)

A 1985 advertisement run by Schiffli Manufacturers & Cutters said, “With the flood tide of imports, we must act if we are to save the embroidery industry. With one out of two garments sold in the United States today imported, business in the American embroidery industry has drastically reduced. We cannot compete against wages as low as 16 cents per hour or even 38 cents, 63 cents, or $1.18 per hour. […] Jobs are being lost daily.”

After the Stevens report, the state began a program to help embroidery companies secure low-cost loans to expand and upgrade their equipment. Unfortunately, that did not help. The industries market share still decreased to 70 percent from about 90 to 95 percent, much of this is due to the North American Free Trade Agreement, which allows Mexico and China to cheaply export their apparel to the US.

(Pristin New York Times 01-03-98)

I had a hard time finding any articles on West New York’s embroidery industry, and as I drove around looking for the factory addresses that I had, many of them had closed their doors.

Sweatshop Become a Huge Problem in WNY

In the 1970s, as more illegal Latino immigrants arrived in West New York and the embroidery industry began to decline because of the ability of overseas factories to hire cheap labor, many of the industries here tried to cut corners. Sweatshops and homeworkers – both against US law—were becoming a large problem.

Sweatshops with 12-hour days, seven-day weeks, wages far below the state minimum, and the violation of occupation safety laws were prevalent in this small New Jersey town. There were children 12 and 13 years old working for 24 dollars per week for 40-hour weeks.

(Brown The Thursday Dispatch 04-21-1977)

The victims of these factories were usually Spanish-speaking, newly arrived immigrants who either did not know enough English or about American culture to know this was against the law, or they were undocumented aliens who feared deportation. In 1977, there were about 10,000 illegal aliens in Hudson County. (Kerr Hudson Dispatch 07-22-77)

A lot of times, owners conceal these operations by sending work out to be done at home where no one sees the cramped apartment with material all over the floor, children running around, and workers getting paid one dollar an hour. “They work in cellars, at home or in converted storefronts for manufacturers who don’t bother to get the required labor permits and avoid paying them the minimum wage of $3.35 an hour,” according to Assistant Commissioner William Clark. (Lamendola The Sunday Star Ledger 04-12-81)

Unions such as the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) and the NJ Department of Labor tried to close down these shops.

A 1930s law governing work at home allows up to five percent of a shop’s employees to be home workers if everyone has the proper licenses. Most of the employees in these shops are Cuban, South American, Puerto Rican, or Italian. Since none of their work is on the books, sweatshop workers are able to collect unemployment and welfare benefits to supplement the substandard wages they receive. Because the sweatshop or home worker labor market is an underground business, it is difficult for labor officials to catch them or even know how many there are. In 1982, officials found 68 firms, most in Hudson County, were violating the homework laws. Firms were fined.

(Lynn Record 03-20-83)

Some of the factories would disappear, closing before the garment workers were paid. While others threatened to call INS on any dissenters.

It is rough for these immigrants who just want to work so that they can eat, and instead, are being punished by officials when these companies close down after being caught and paying high fines. Yet, the closing of sweatshops is for the best. These foreign-born workers, particularly in the garment industry, are proud people who refuse to go on welfare rolls, preferring to labor long hours for low wages.

A lot of the time, women must complete a rushed job; in this case, children as young as 6 years old and husbands often pitch in to help.

The US Department of Labor defines a sweatshop as a business that is guilty of “repeated, egregious” violations of wage, child labor, health, and safety laws.

Most of the blame for sweatshops goes to the stores that buy these products. It is the store’s constant push to find the cheapest product without compromising quality is to blame for this labor issue. West New York was the key place for producing products for stores as small as the mom-and-pop store on Bergenline Ave to producing products for large stores like J.C.Penny.

Many of the garment shops that used to be located in West New York and throughout Hudson County were replaced by fly-by-night shops in the 90s that would close up without notifying workers, owing them months back in wages. Most of the time, owners are hard to catch before they leave the country.

Union and labor officials, even today, walk around Hudson County, making sure that people are working within the US laws.

Conclusion

Latinos in West New York transformed a ghost town into an economic mecca of industry, food, and Latin tastes. For the most part, WNY’s only major labor issue was the sweatshops. For the most part, the diversity that Latinos bring to the area has altered this town of lower working class to one that people gravitate towards for the tastes of the homeland.

The bulk of the information in this article is on the Cuban population because it was almost impossible to find information on the other Latino groups. More in-depth research should be done on the more recent Hispanic immigration that is and has been occurring.

I feel like the amount of people who work in New York City but reside in West New York is not accounted for enough in the material that I found. For example, in 1990, 10,454 persons of Hispanic origin worked outside of their area of residence compared to 3,282 who worked in West New York.

Times are changing, and more and more immigrants are going to college and working in offices, so the demographic patterns of West New York are changing as the next generation moves up the socio-economic scale.

The text is copyrighted by the author, 2025.

Users may cite with attribution.

Appendix I: Census Data 1930-2000

Appendix II: Census of Manufacture 1930-1990 & List of WNY Embroidery Factories

Appendix III: Strikes in West New York

Bibliography

Cooney, Rosemary Santana. Adaptation and Adjustment of Cubans: West New York, New Jersey. (Monograph no. five). Hispanic Research Center, Fordham University, Bronx, New York: 1980.

Gil, Rosa Maria. (1962). The Assimilation And Problems Of Adjustment To the American Culture of One Hundred Cuban Refugee Adolescents, Attending Catholic and Public High Schools, in Union City and West New York, New Jersey, 1959-1966. Master of Social Work dissertation, Fordham University School of Social Service, New York: 1968.

Pelaez, Sister Armantina R., F.M.S.C. The Cuban Exodus. Dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a B.A., Ladycliff College. Highland Falls, NY: 1973.

Rogg, Eleanor Meyer. The Assimilation of Cuban Exiles: The Role of Community and Class. Aberdeen Press. New York: 1974.

Rogg, Eleanor. “The Influence of a Strong Refugee Community on the Economic Adjustment of Its Members”. International

Migration Review, Vol. 5, No. 4, Naturalization and Citizenship: US Policies, Procedures and Problems. (Winter, 1971), pp. 474-481.

Rogg, Eleanor. The occupational adjustment of Cuban refugees in the West New York, New Jersey area. Thesis at Fordham University, Bronx, NY: 1970.

Town of West New York Planning Board. “Existing Population characteristics”. Community Housing & Planning Associates, Inc. August 1975.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census of the Population and Housing: 1930-1990. Census Tracts. Final Report PHC(1)-96 Jersey City, N.J. SMSA

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census of the Population 1930-1990. New Jersey.

Articles

“Accord Averts Strike”. New York Times. 18 Aug. 1948: 50.

“Bank Strike Due Today.” New York Times. 6 Jan. 1947:23.

“Story of W. New York: Sheer Embroidery.” Jersey Journal. 8 July 1948: 40.

“Strike In Bank Averted.” New York Times. 7 Jan. 1947: 23.

“Suit Makers Strike.” New York Times. 10 Jan. 1933: 40.

“Knit Goods Strike Met By A Lockout.” New York Times. 9 Aug. 1934: 2.

“West New York.” West New York: Bicentennial. 1939: 39.

“Worry About Us,’ Lace Area Pleads”. New York Times. 3 Feb. 1955: 5.

Ascarelli, Miri. “As Good Jobs Move Out, Sweatshops Move In.” Jersey Journal. 10 Sept. 1996: A1.

Ascarelli, Miri. “Fashion Slaves.” Jersey Journal. 11 Sept. 1996: A1.

Brown, Susan. “Garment Sweatshops Resurge in Hudson.” The Thursday Dispatch. 21 Apr. 1977: 20CF.

Canal, Alberto. “Que Pasa en Hudson.” Jersey Journal.

Escobar, Gabriel. “Hispanics Hold Ballot Balance of Power.” Hudson Dispatch. 20 Jan. 2006: 1.

Ferratti, Fred. “Bergenline Ave., the Pasta of Times, the Wurst of Times.” New York Times. 30 Jul. 1976: 53.

Forero, Juan. “How Two From Cuba Reshaped a County.” Star Ledger. 8 Aug. 1999: 1.

Juster, Jacqueline. “Our Hispanic Heritage.” New Jersey Business. 2000: 22.

Kerr, Kathleen. “NJ Sets Hudson Sweatshop Probe.” Hudson Dispatch. 22 July 1977: 1.

Koshetz, Herbert. “Embroidery Invades Even the Casual Fashions.” New York Times. 7 Mar. 1971: F17.

Kenny, Camille. “The New Immigrants.” Hudson Dispatch. 21 May 1998.

Lamendola, Linda. “Home Sweatshops Cited in Garment Trade.” The Sunday Star-Ledger. 12 April 1981: 1-16.

Louie, Elaine. “A Pan-American Highway of Food on Avenida Bergenline.” The New York Times. 30 Apr. 1997: C3.

Lynn, Kathleen. “Exploiters Make a Stitch a Crime.” The Record. 20 March 1983: A-1.

McLane, Daisann. “Along 90 Blocks of New Jersey, A New World of Latin Tastes.” The New York Times. 11 Dec. 1991: C1

Narvaez, Alfonso A. “50,000 Cubans Add Prosperity and Problems to New Jersey.” New York Times. 24 Nov. 1974: 43.

Narvaez, Alfonso A. “Jersey’s Cubans Look to US for Help in Aiding Refugees.” New York Times. 14 Nov. 1980: B1.

Nieves, Evelyn. “A Contract Out on Workers’ Rights.” The New York Times. 18 Oct. 1994: B6.

Nieves, Evelyn. “Union City and Miami: A Sisterhood Born of Cuban Roots.” The New York Times. 30 Nov. 1992:B1.

Ondetti, Gabriel. “Blending into the Melting Pot.” Jersey Journal. 6 July 1993: 1.

Perez, Miguel. “Their Dream has Become A Nightmare.” Daily News. 27 Aug. 1980: 25.

Rangel, Jesus. “Cuban Refugees Adjust to Life in New Jersey.” The New York Times. 26 Nov. 1987: B1.

Reid, Kenneth. “New Challenge for ‘Little Havana’.” The Sunday Star-Ledger. 1 March 1981.

Rofe, John. “Clamor of Needles is Fading Out.” Hudson Dispatch. 4 March 1988: 3.

Roman, Ivan. “A New Cuban Exodus.” Miami Herald. 1 Oct. 1989.

Romano, Jay. “A Sense of Place.” The New York Times. 28 Nov. 1993: NJ19.

Rosero, Jessica. “Thank for Smoking: West New York Was Once Home to Largest Pipe House.” Hoboken Reporter. 17 Dec. HobokenReporter.com18 Dec. 2006. <http://www.HobokenReporter.com>

Pristin, Terry. “In New Jersey, a Delicate Industry Unravels.” The New York Times. 3 Jan. 1998: B1.

Savage, Ania. “Jobless Pay: Fewer Trips.” New York Times. 6 Apr. 1975: 80.

Sloane, Leonard. “Tides of Fashion Delight Weavers of Schiffli Lace.” New York Times. 11 Jun. 1964: 43.

Special to the New York Times. “Hudson.” New York Times. 7 Sept. 1965: 32.

Special to the New York Times. “Looking for Embroidery? Look in Hudson County.” New York Times 30 Apr. 1972: 96

Spector, Barbara. “Cuban Influx Causes Hudson School Crisis.” Newark Evening News. 10 March 1968: 1.

Speert, Josh A. “The Embroidery Industry: Sew Many Years of Excellence.” New Jersey Business. May, 1998: 58.

Strunsky, Steve. “For 125 Years, a Big Industry That Produces Delicate Lace.” The New York Times. 31 Aug. 1997: NJ3.

The New York Times. “A Town Searches for a Piece of Its Past.” The New York Times. 12 Apr. 1998: 28.

Town of West New York. “Shopping Latino on Bergenline Avenue.” West New York: Visitors Guide. 2000.

Vidal, David. “In Union City, the Memories Of the Bay of Pigs Don’t Die.” New York Times. 2 Dec 1979. Section: The Region.

Zarate, Vincent R. “Hispanic Congress Accuses State of Hiring Bias.” The Star-Ledger. 27 March 1984.