Between Iron and Borders: The Brazilian Community in the Ironbound District of Newark, NJ

Gilson Mateus

M.A. Student in History in the Graduate Program in History at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN).

Introduction

The aroma of cheese bread from the LS Bakery mingles with the humid air rising from the Passaic River. On Ferry Street, the epicenter of the Ironbound district in Newark, New Jersey, Portuguese, with accents that betray Governador Valadares, Ipatinga, or the interior of Goiás, dominates the soundscape. We are just a few kilometers from Manhattan, but the atmosphere is that of a vibrant Brazilian city.

This phenomenon is not merely an immigrant neighborhood; it is the classic definition of an ethnic enclave. Sociologically, an enclave is more than a demographic concentration; it is a “spatial cluster with a concentration of ethnically owned commercial enterprises” (Portes and Jensen, 1989, p. 930), where social and economic life can be conducted almost entirely in the mother tongue. Ironbound is the embodiment of this. Although exact census data for the district are difficult to isolate, the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) consistently demonstrates that Newark is a major destination for Brazilian migration, housing tens of thousands of individuals born in Brazil or of Brazilian descent (US Census Bureau, 2023).

Quantifying this community is methodologically complex. The primary source is the US Census Bureau, which collects data through the American Community Survey (ACS), a detailed annual survey. The raw data and tables can be publicly accessed through the Census data portal. To find relevant data, the researcher can search for “Ancestry” or “Place of Birth” tables for the geography “Essex County, New Jersey” or “Newark city, New Jersey”.

The Census shows us a crucial demographic reversal. 2022 ACS data (5-year estimate) for Essex County (where Newark is located) indicates that the population of Brazilian descent (approximately 14,966) has already numerically surpassed that of Portuguese descent (approximately 13,729). This solidifies the neighborhood’s transition from “Little Portugal” to “Little Brazil” (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023).

It is an academic consensus that Census data, although official, significantly underreport the immigrant population, especially the Brazilian immigrant population. As classic studies on migration point out (Massy; Durand, 2005), fear of deportation, language barriers, and high residential mobility cause undocumented immigrants to avoid responding to government surveys. Estimates from the Brazilian Consulate and community organizations frequently place the floating population in the Newark metropolitan area at much higher numbers, sometimes double or triple that recorded by the Census. The iron sector, therefore, is today a segmented labor market: abundant in jobs that require physical effort and long hours, but which coexist with the precariousness and statistical invisibility of a significant portion of its workforce.

This article proposes to analyze the Brazilian community of Ironbound through the paradox suggested in its title: Between Iron and Borders. Iron is the visible legacy of the neighborhood. The name Ironbound refers to the railroads that, in the 19th century, delimited the district and served its factories and foundries. This Iron attracted the first waves of European immigrants (Portuguese, Polish, Italian) and today represents the labor structure that attracts Brazilians: the hard, exhausting work in construction, cleaning services, and restoration. Borders are the multifaceted challenges that define the immigrant experience in the 21st century. It’s not just about the geographical border overcome upon arrival, but about the daily barriers: the border of legality, which implies, for example, immigration status, governing access to rights and vulnerability; the cultural and linguistic border, and the socioeconomic frontier.

Therefore, this article investigates how the Brazilian community in Ironbound negotiates its socioeconomic integration and constructs its identity, while simultaneously being anchored in the Iron structure of a historic working-class neighborhood and pressured by the borders of contemporary immigration.

A Palimpsest of Migrations: The Industrial Ironbound

The name Ironbound, etched into the heart of Newark, New Jersey, resonates with a poetic and material duality. It evokes, in one breath, the heritage of an industrial America, forged in iron and soot, whose railroads still define the district as an urban island. At the same time, the name serves as a powerful metaphor for the immigrant experience: a journey defined by geographical, legal, cultural, and economic borders that demand an iron will to overcome. It is in this setting of metal and memory that, starting in the late 1970s, a vibrant Brazilian community began to take root, transforming a declining working-class neighborhood into an epicenter of the Latin American diaspora in the United States. What was once a predominantly Portuguese and Polish enclave reinvented itself as a “piece of Brazil”, a living testament to cultural resilience and the ongoing negotiation of what it means to belong.

To understand the magnitude of the transformation brought about by the Brazilian community, it is imperative first to excavate the historical layers of Ironbound itself. The district was not a blank canvas, but a palimpsest of successive migratory waves that shaped its character long before the arrival of the first Brazilians. Newark, in the 19th and early 20th centuries, was an industrial powerhouse. Its factories produced a variety of goods, such as leather and beer, and its strategic location, surrounded by railroads, made it a vital hub in the East Coast economy.

This industrial prosperity attracted a workforce from Europe. Germans, Irish, Poles, Italians, and, crucially, Portuguese, settled in the neighborhood, building churches, social clubs, and shops that served their communities. The Portuguese, in particular, created an embryonic Lusophony that would prove fundamental, establishing the basis for an ethnic social capital (Portes & Sensenbrenner, 1993) that would inadvertently facilitate the adaptation of future Brazilian migrants.

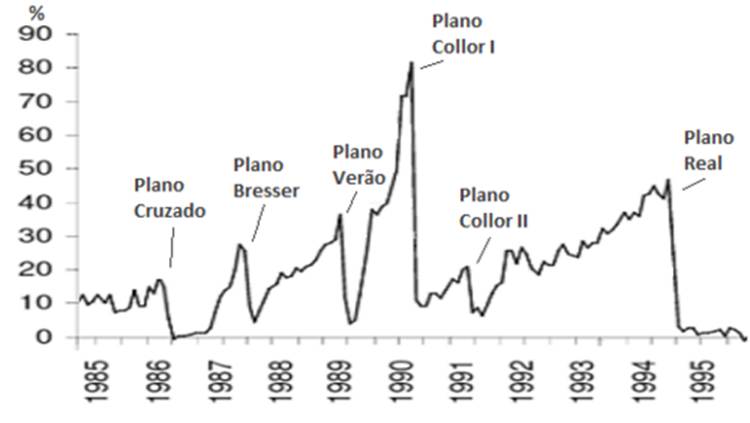

The second half of the 20th century brought deindustrialization. Factories closed, and Newark, like so many other cities in the Rust Belt, entered a period of decline. It was in this scenario of abandonment and opportunity that Brazilians began to arrive. The context in Brazil was unique in its push. The supposed “economic miracle” of the military dictatorship had run its course, giving way to the “lost decade” of the 1980s, marked by hyperinflation, political instability, and chronic unemployment.

As widely studied in recent Brazilian historiography of the late 20th century, this period was marked by chronic instability that eroded purchasing power and destroyed prospects, especially for the urban middle class and small business sectors. Although hyperinflation was a constant backdrop, the catalyst that transformed insecurity into actual migration was the drastic Collor Plan in 1990. The confiscation of savings, an extreme form of state intervention, not only liquidated the capital of families and businesses but also irrevocably broke the population’s trust in the country’s financial institutions, generating what sociologist Teresa Sales (1999) describes as a feeling of disenchantment and a need to seek alternatives outside of Brazil.

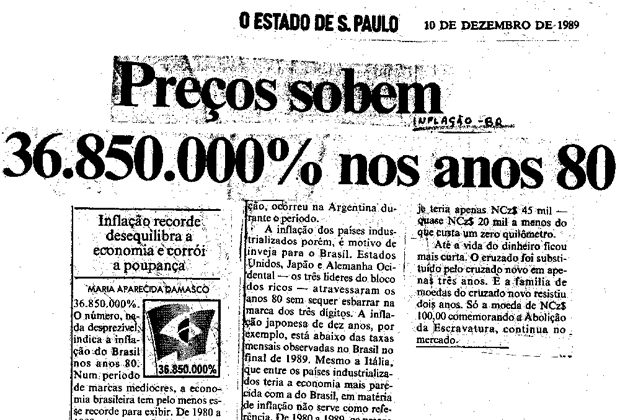

Figure 1 – News report from the Estado de São Paulo newspaper announcing hyperinflation.

Source: Damasco, Maria Aparecida. O Estado de S. Paulo, edition of December 19, 1989.

Figure 2 – Graph of Hyperinflation in Brazil (1985-1995)

Source: Data from the National Consumer Price Index (IPCA): rate of change” (Code: PRECOS_IPCAG), whose primary source is the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE/SNIPC)

Given this scenario, migration became a strategy for survival and social mobility. The concentration of Brazilians in the Ironbound district of Newark, New Jersey, is a classic example of chain migration, facilitated by pre-existing social and ethnic networks. As exhaustively documented by anthropologist Maxine Margolis (1994), Ironbound already hosted a robust and established Portuguese community. This Lusophone infrastructure, comprising businesses, churches, and associations, functioned as a vital reception network, offering newly arrived Brazilians not only their first jobs in sectors such as construction, restaurants, and cleaning services but also a cultural and linguistic support system that mitigated the shock of immigration and facilitated adaptation. Thus, the hyperinflation crisis acted as the primary force of expulsion. At the same time, the networks of ethnic affinity in Ironbound channeled this flow, transforming the neighborhood into the most iconic enclave of the Brazilian diaspora in the United States.

Unlike other Latin American diasporas, Brazilian migration was, in its overwhelming majority, an economic undertaking. The pioneers, many of whom originated from cities like Governador Valadares in Minas Gerais, were not essentially adventurers seeking new experiences in a foreign land, but rather people in a situation of economic hardship. The Ironbound was a logical destination. The Portuguese presence provided comfort, particularly linguistic comfort, for migrants who did not speak English. The first Brazilians found employment in low-skilled sectors, discreetly integrating into the existing landscape.

Faced with the rigidity of the iron structure of the labor market and the constant pressure of legal and social boundaries, the Brazilian community in Ironbound did not react passively; it acted actively, building its own universe. This response is not assimilation or surrender, but rather a vibrant reconfiguration of urban and social space in its own image. The result is the transformation of Ironbound from a mere workplace into a territory, a symbolic home.

The primary strategy for this is the creation of a robust ethnic economy. Ferry Street, with its succession of restaurants, bakeries, butcher shops, import stores, and money transfer agencies, embodies what geographers call placemaking. These businesses, more than simple commerce, function as institutional anchors: they are the first employers of newcomers, the places where vital information is exchanged, and the spaces where Brazilianness is consumed and reaffirmed daily. By creating an internal economy, the community partially mitigates the professional disqualification imposed by the socioeconomic border; the engineer who cannot practice his profession can, at least, open a thriving business within the enclave.

Alongside commerce, no institution is more central to the organization of Brazilian life in the Ironbound than faith. Although the historical Portuguese community established Catholic churches, the Brazilian religious landscape is dominated by a myriad of evangelical churches, especially neo-Pentecostal ones. As documented by Ana Cristina Martes (2000), these churches transcend their spiritual function. They are the primary source of social capital, providing an immediate safety net for the most vulnerable, particularly undocumented individuals. The church functions as an employment agency, a psychological counseling center, and sometimes even as an informal guarantor of housing.

In a context where the State is a threat, the church becomes the center of civic life. Ultimately, the community responds to physical borders by redefining them through technological advancements and economic developments. The immigrant’s life in the Ironbound is not contained within Newark; it is fundamentally transnational. The community operates in a “social space that transcends geographical, political, and cultural boundaries” (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Szanton Blanc, 1994). The iron of New Jersey is used to build the future in Brazil. The constant flow of financial remittances, the dollar houses in Governador Valadares, the daily calls via messaging apps, and the omnipresent dream of return (even if never realized) demonstrate that the border, for the immigrant, is porous. The Ironbound is not the final destination; it is a transit station, halfway between the Brazil that was left behind and the Brazil that one wishes to build with the money earned in the iron.

Outbound: Historical Demography in Perspective

The Ironbound district is not an official Census geography, which necessitates the use of approximations. More accurate data is available at the Newark city and Essex County levels, where Ironbound is located, primarily corresponding to the city’s East Ward.

The most significant demographic characteristic of Ironbound over the last three decades is ethnic succession, specifically the transition from a predominantly Portuguese enclave to a predominantly Brazilian demographic space, as already discussed. Portuguese immigration peaked in the 1960s and 1970s, establishing institutions such as clubs, restaurants, bakeries, etc., which, ironically, would facilitate the arrival of the Brazilian wave after the 1980s (Goes; Martes, 2018). Brazilians were attracted by a Lusophone infrastructure that eliminated the initial language barrier.

The most recent data from the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Estimates (2018-2022) confirm this demographic reversal. Although the numbers seem low, mainly due to underreporting and dispersion across the county, the trend is clear. In Essex County, the population of Brazilian descent has already surpassed that of Portuguese descent.

Table 1 – Population by Stated Ancestry (Essex County, NJ)

| Ancestry Group | Estimated Population (2022) |

| Brazilian | 14,966 |

| Portuguese | 13,729 |

Source: US Census Bureau, ACS 2022 5-Year Estimates, Table B04006.

This table shows that, in terms of self-declared identity, Brazilians are now the numerically dominant Portuguese-speaking group in the central Newark region. More critical than ancestry, for understanding the enclave, is linguistic demographics. The Ironbound functions as a bubble because a critical mass of people speak Portuguese. The Census data for the city of Newark, where the majority of Portuguese speakers are concentrated in the Ironbound, is revealing.

Table 2 – Language Spoken at Home (Population 5+ years) (Newark, NJ)

| Language Spoken at Home | Estimated Population (2022) |

| Portuguese | 23.155 |

| Spanish | 114,614 |

| French Creole (Haitian) | 10.375 |

Source: US Census Bureau, ACS 2022 5-Year Estimates, Table B16001.

What is demographically crucial is not just how many speak Portuguese, but how many depend exclusively on it. The Census also measures Limited English Proficiency (LEP), defined as speakers who report speaking English less than very well. In the city of Newark, out of 23.155 Portuguese speakers, a staggering 11.231 (or 48.5%) are classified as having limited English proficiency. This statistic is demographic proof of the enclave: nearly half of Newark’s Portuguese-speaking population does not master English, making Ferry Street’s infrastructure of Portuguese-based businesses, churches, and services not a convenience, but an absolute necessity for economic and social survival.

This demographic profile, characterized by youth, employment, and language barriers, is directly shaped by the legal border. Sociologist Ana Cristina Martes (2000) and other migration researchers, such as Douglas Massey and Massey Durand (2005), argue that the Census fails to capture the undocumented population. This population, by definition, avoids contact with the government. Therefore, the 23.000 officially registered Portuguese speakers should be seen as the floor, not the ceiling, of the Brazilian presence, which local organizations and the consulate often estimate to be double or more in the metropolitan area.

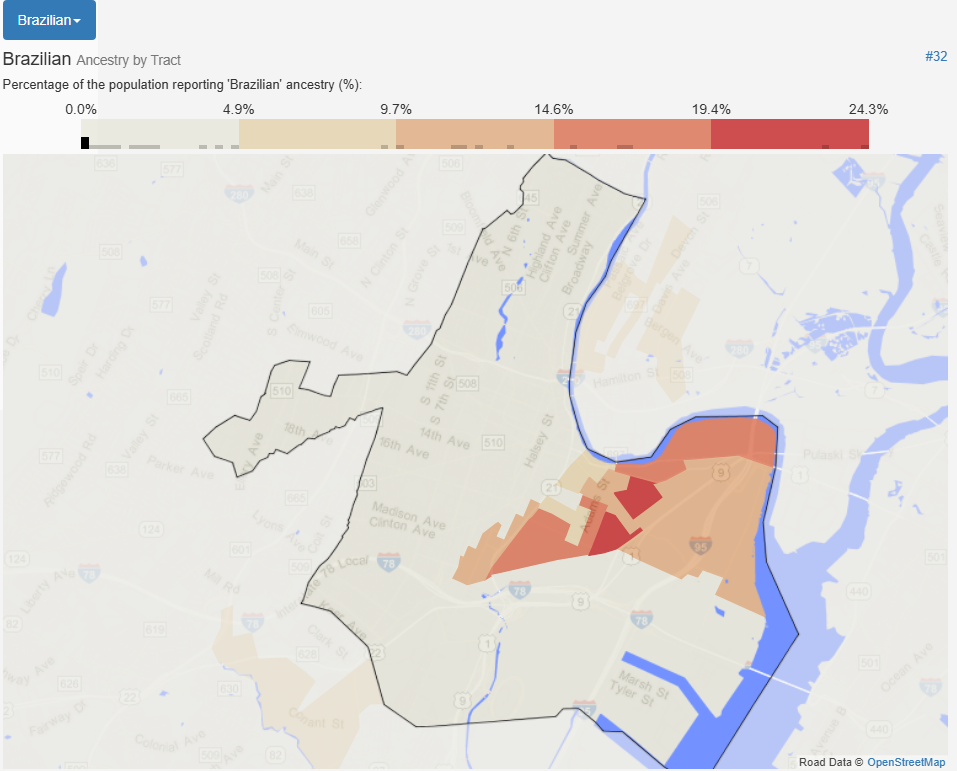

The visual data provided by the Statistical Atlas, which uses the US Census Bureau as its source, enables us to accurately map the transformation of the “Little Portugal” neighborhood into the Luso-Brazilian epicenter it is today.

Figure 3 – Composition of declared ancestry in Newark, NJ, by percentage and count.

Source: Statistical Atlas, Ancestry in Newark, New Jersey (City), based on data from the US Census Bureau (ACS 5-Year Estimates)

The analysis of the ancestral composition of the city of Newark, as illustrated in Figure 3, serves as the fundamental starting point for this study. This graph reveals that the populations of Portuguese descent (3.7%, or 10,300 people) and Brazilian descent (3.3%, or 9,123 people) are statistically almost equivalent. This data is quantitative proof of the central thesis of authors such as Goes and Martes (2018): Brazilians did not replace the Portuguese, but rather superseded them, attracted by the pre-existing Lusophone infrastructure. Together, these two groups form a 7% bloc of the city’s population, creating the critical mass necessary to sustain the linguistic and cultural enclave.

More revealing than the total count, however, is the location of this population. The map in Figure 4 (Brazilian Ancestry by Tract) is the most potent visual evidence. It demonstrates that this population of 9.123 Brazilians is not randomly dispersed throughout Newark. On the contrary, it is hyper-concentrated precisely in the geographic area east of Penn Station, which defines the Ironbound. The Ironbound census tracts appear in shades of dark red, indicating that the concentration of Brazilians reaches 19.4% and even 24.3% in some central regions.

Figure 4 – Map of Concentration of Brazilian Ancestry by Census Tract in Newark

Source: Statistical Atlas, Ancestry in Newark, New Jersey (City)

This is the exact visual definition of an ethnic enclave, as conceptualized by Alejandro Portes: a “spatial cluster” that facilitates the development of an internal economy (Portes; Jensen, 1989). The reason Ferry Street can support dozens of Brazilian businesses is that, as the map proves, almost one in four people living in the surrounding blocks are of Brazilian origin.

It is methodologically crucial, however, to articulate these official data with academic criticism regarding underreporting. The 9.123 Brazilians counted by the Census, as shown in Figure 3, are mostly citizens or legal residents. As the vast literature on migration points out, including the works of Martes (2000) and Massy and Durand (2005), the undocumented population, a central component of the legal border we are discussing, is structurally invisible to census takers. The fear of deportation and high residential mobility mean that the official number is only the floor (the minimum), and not the ceiling, of the demographic presence. The actual floating population is, by academic consensus, significantly larger.

Finally, the comparative graphs presented in Figures 5 and 6, respectively, provide context for the Ironbound region. The graph in Figure 5 shows that the concentration of 3.3% in Newark is almost triple that of Essex County (1.3%) and much higher than that of New Jersey (0.4%), confirming Ironbound as the state’s epicenter. The graph in Figure 6 (Ancestry by Place, Northeast) depicts Newark as part of a larger diaspora in the Northeast, competing in concentration with cities like Danbury, CT (6.1%) and Lowell, MA (2.9%), which have historically been known as destinations for Brazilians.

Figure 5 – Brazilian Ancestry Chart (Comparison between Newark and Essex)

Source: Statistical Atlas, Ancestry in Newark, New Jersey (City)

Figure 6 – Graph of Brazilian Ancestry (Comparison of Northeastern Cities)

Source: Statistical Atlas, Ancestry in Newark, New Jersey (City)

Meanwhile, the visual data from the census paint a clear demographic picture: the history of Ironbound is one of Lusophone succession, where the Brazilian population concentrated so densely that it allowed the creation of a robust enclave. The official numbers, although underreported, prove the existence of this agglomeration, which is the demographic base that gives life to iron (the work) and meaning to the frontiers (the challenges) of the community.

Not to conclude…

In short, the Brazilian community in Ironbound, Newark, embodies the paradox suggested by the tension between Iron and Borders. The iron of industrial legacy and working-class labor attracted immigration, while the borders of legality, language, and professional disqualification imposed severe limits. As the analyzed demographic data demonstrate, the Brazilian response to this tension was not assimilation, but spatial concentration. The formation of a dense ethnic enclave, visually evident in census tract maps, enabled the creation of a vibrant internal economy, robust religious institutions, and a Lusophone social life that serves as a protective shield against external pressures, transforming a historic working-class neighborhood into a territory of cultural and economic resilience.

This territory, however, is not static. Analysis reveals that the community lives a fundamentally transnational existence, where the iron of labor in New Jersey fuels a life project focused on Brazil, evidenced by the massive flow of remittances. Ironbound is not a final destination, but a functional platform. However, the future of this enclave faces new challenges: the rise of a second generation, whose relationship with Brazilian identity will shape the enclave’s continuity, and the economic pressure of gentrification, which threatens to displace the very working-class community that gave new life to the iron industry in Newark.

References

Basch, Linda, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc. 1994. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach.

Damasco, Maria Aparecida. 1989. Prices rose 36,850,000% in the 80s: O Estado de S. Paulo, 10 de dezembro de 1989.

Goes, Rosana, and Ana Cristina Martes. 2018. Brazilians in Newark: The Emergence of an Ethnic Enclave. Novos Estudos CEBRAP 37 (1): 117–38.

Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). sd National Consumer Price Index (IPCA): rate of change (PRECOS_IPCAG). IBGE Automatic Data Retrieval System (SIDRA).

Margolis, Maxine L. 1994. Little Brazil: An Ethnography of Brazilian Immigrants in New York City. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Martes, Ana Cristina. 2000. Brazilians in the United States: a study on immigrants in Massachusetts. São Paulo: Paz e Terra Publishing House.

Massey, Douglas S., and Jorge Durand. 2005. Behind the Plot: Migration Policies between Mexico and the United States. Zacatecas: Universidad Autónoma de Zacatecas.

Portes, Alejandro y Leif Jensen. 1989. The Enclave and the Entrants: Patterns of Ethnic Enterprise in Miami Before and After Mariel. American Sociological Review 54 (6): 929–49.

Portes, Alejandro, and Julia Sensenbrenner. 1993. Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action. American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1320–50.

Sales, Teresa. 1999. Brasileiros longe de casa. São Paulo: Cortez Editora.

Statistical Atlas. n.d. “Ancestry in Newark, New Jersey (City).” Based on data from the US Census Bureau (ACS 5-Year Estimates).

US Census Bureau. 2023. American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates (2018-2022). Table B04006, “People Reporting Ancestry,” and Table B16001, “Language Spoken at Home for the Population 5 Years and Over.” data.census.gov .