Notes

1 The origin of the neighborhood’s name is not clear, though there may have been some connection of early 20th century residents to the Spanish-Cuban-American war in 1898; American soldiers fought a decisive battle against the Spanish at San Juan Hill near Santiago, Cuba. In any case, the origin of the name does not have to do with San Juan, Puerto Rico.

2 See Samuel Zipp, “The Battle of Lincoln Square” in Manhattan Projects: The Rise and Fall of Urban Renewal in Cold War New York (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012). The term “creative destruction” comes from Max Page, The Creative Destruction of Manhattan, 1900-1940 (University of Chicago Press, 1999).

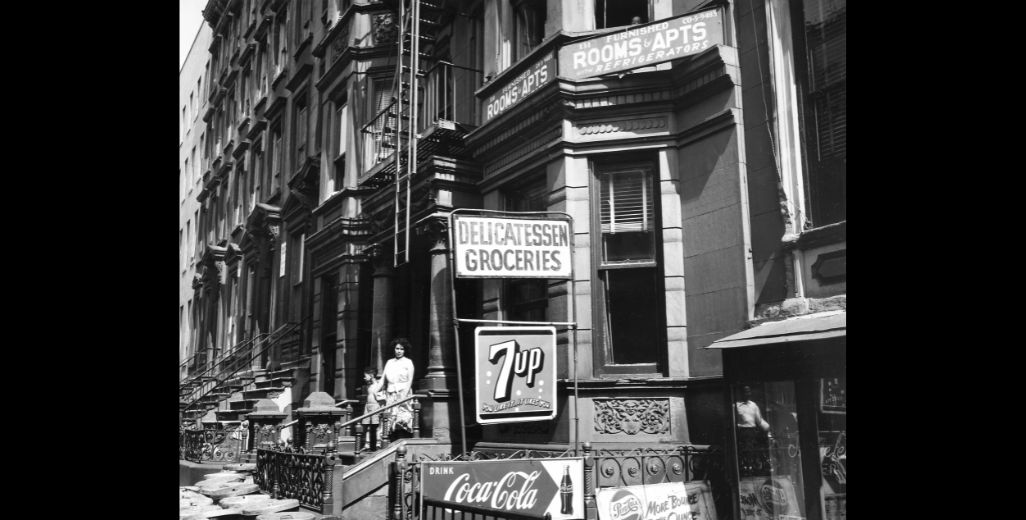

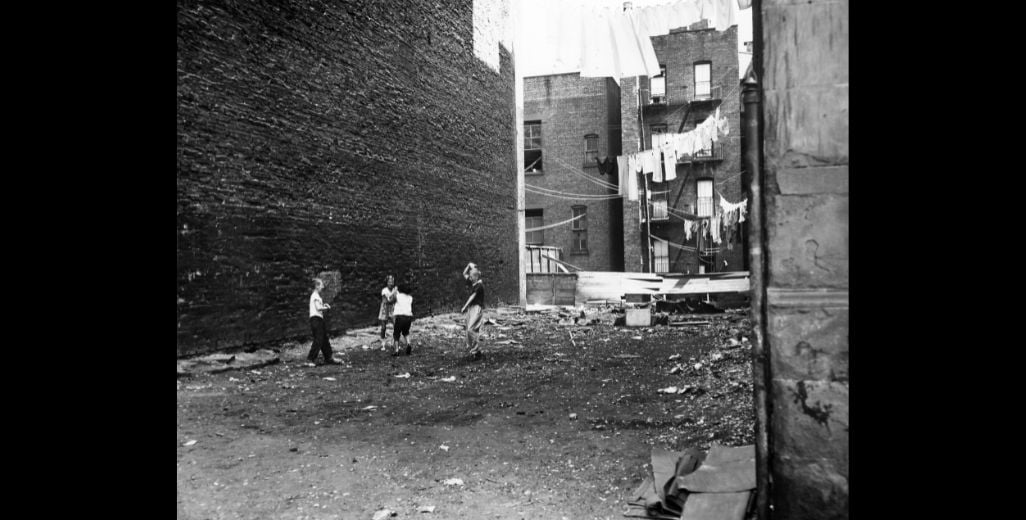

3 Dan W. Dodson, Between Hell’s Kitchen and San Juan Hill — A Survey (Human Relations Studies, Inc., 1952), pp. 10, 16. This survey covered an area immediately southwest of Columbus Circle, not San Juan Hill itself; but according to contemporaneous sources, the housing stock of the blocks just north and just south of Columbus Circle were very similar.

4 Housing development related to this provision of the 1949 Housing Act was often referred to simply as “Title I”; Title II increased FHA mortgage insurance; Title III committed the federal government to building 810,000 new public housing units, and Title V allowed the Farmers Home Administration to grant mortgages to encourage the purchase or repair of rural single-family homes.

5 Robert Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Random House, 1974), 706, 777.

6 “Title I Projects Total 13 in City,” New York Times, April 13, 1959, p. 33.

7 “President Turns Earth to Start Lincoln Center,” New York Times May 15, 1959, 1.

8 Note: the “kitchen debate” between Vice President Nixon and Soviet premier Khrushchev took place at the U.S. embassy in Moscow two months later, in July 1959, and served as an even more visible example of Eisenhower’s message.

9 In A Raisin in the Sun, published and produced by Lorraine Hansberry in 1959, the character Ruth describes the high cost of housing for Black Chicagoans: “…Lord knows, we’ve put enough rent into this here rat trap to pay for four houses by now…” (New York: Vintage Books, 1994 [1959]), 44.

10 Richard Rothstein, “De Facto Segregation: A National Myth” in Molly Metzger and Henry Webber, eds., Facing Segregation: Housing Policy Solutions for a Stronger Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 17-18.

11 Dodson, Between Hell’s Kitchen and San Juan Hill (A Survey) (1952), 12.

12 A sample of articles published by the New York World-Telegram in 1947 includes: “Puerto Rico to Harlem – At What Cost?” May 1, 1947; “Little Puerto Rico, a Gigantic Sardine Can,” May 2, 1947; “Puerto Rican Influx Overcrowds Schools,” May 3, 1947; “Migrants Find Even More Misery in City,” Oct. 20, 1947; “Migrants Hike Relief,” Oct. 22, 1947; “Crime Festers in Bulging Tenements,” Oct. 23, 1947.

13 César Andreu Iglesias, ed., Memoirs of Bernardo Vega: A Contribution to the History of the Puerto Rican Community in New York (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1984).

14 A prototype for the Migration Division was the Office of Employment and Identification, opened in East Harlem in 1931, to help Puerto Rican migrants find jobs during the Depression. Another office in the early 1950s was located near the 60th St. office, at 88 Columbus Avenue.

15 Dodson, Between Hell’s Kitchen and San Juan Hill (A Survey) (1952), 12.

16 Resources included pamphlets on topics like “Rights and Responsibilities of Tenants and Landlords”; migrants were advised of their rights via printed guidelines on voting, obtaining a driver’s license or marriage license, and registering children for school.

17 Charles Abrams, “How to Remedy our ‘Puerto Rican Problem,’” Commentary 19 (February 1955): 120-127. [121,123]

18 Draft letter from Robert Moses to J. Monserrat re: SLUM CLEARANCE, September 9, 1958; letter from Fracisca Bou to Robert Moses, September 22, 1958. Robert Moses papers, box 117, NYPL.

19 Zipp, Manhattan Projects, 205-208.

20 Dan Wakefield, Island in the City: The World of Spanish Harlem (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1959), 232, 236.

21 Jesús Colón, “The Growing Importance of the Puerto Rican Minority in N.Y.C.,” [1955], Colón papers, Series III, box 2, folder 1, Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College.

22 Wakefield, Island in the City, 265; “Postel Sworn to Bench Post,” New York Times, April 24, 1957, 37; Dan Wakefield, “Politics and the Puerto Ricans,” Commentary, Jan. 1, 1958, 226-236.

23 Frances Negron-Muntaner, “Feeling Pretty: West Side Story and Puerto Rican Identity Discourses,” Social Text 63 (summer 2000): 83-106.

24 Samuel Zipp, Manhattan Projects, 157-158; Linda Murray, “Original ‘West Side Story’ Production Photo Captures Robert Moses’s Urban Renewal Landscape,” Gothamist, Sept. 14, 2021. https://gothamist.com/arts-entertainment/west-side-story-movie-robert-moses-urban-renewal-lincoln-center

25 One judge asserted that to deny Fordham the opportunity to participate in a federally funded redevelopment program simply because it was a “sectarian institution” would be “to convert the constitutional safeguards into a sword against the freedoms which they were intended to shield.” “Fordham U. Share in Lincoln Square Is Upheld by Court,” New York Times Dec. 24, 1957, p. 1 on state Supreme Court opinion; see also Appellate Court’s “Text of Court Ruling on Lincoln Square,” New York Times, May 2, 1958, p. 17.

26 Harris Present, letter to George M. Johnson, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Feb. 3, 1959. [Hearings, Housing, vol. 2] Present proposes “that no slum clearance project be approved unless…there be new housing built for the residents of that slum area within their economic means in a desirable location (not necessarily on the previous site).”

27 Peter Kihss, “Puerto Rican Story: A Sensitive People Erupt,” New York Times, July 26, 1967, 20.

28 When Senator Walter Mondale, chair of the Senate Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity, invited López Antonetty and about twenty other Puerto Rican leaders to testify before the committee in 1970, the issue of housing was raised repeatedly. “Hearings before the Select Committee on Equal Educational Opportunity of the United States Senate,” 91st Congress, 2nd Session, November 23-25, 1970 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970).

29 “Reagan Urges Blacks to Look Past Labels and Vote for Him,” New York Times, Aug. 6, 1980, A1.